Source: Dolphin Business Research Institute

Powell's latest speech released a heavy signal of the Federal Reserve's monetary policy.

On May 15, local time, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell attended the Second Thomas Laubach Research Conference and delivered a speech. He said that as the economy and policies continue to change, long-term interest rates may rise. He warned: "We may be entering a period of more frequent and potentially more persistent supply shocks-this is a daunting challenge for both the economy and the central bank."

At the same time, Powell also revealed that the Federal Reserve is adjusting its overall policy-making framework to respond to major changes in the outlook for inflation and interest rates after the epidemic in 2020, and plans to complete the review of specific modifications to the framework in the next few months.

When will the Federal Reserve cut interest rates?

According to the Securities Times, the seminar that Powell attended this time was more of an academic discussion, so he did not mention much about the economic outlook and inflation. But from his speech, the transmission mechanism of inflation to interest rates has always been the most important consideration for the Federal Reserve to formulate monetary policy.

Last week, the Federal Reserve announced that it would maintain the target range of the federal funds rate at 4.25%-4.5% unchanged, and said that the US economy faces an increased risk of rising unemployment and inflation. Many Wall Street banks predict that the Federal Reserve will not cut interest rates before December this year or later.

The latest data shows that the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 2.3% year-on-year in April this year, better than market expectations and the lowest year-on-year increase since the beginning of 2021. The personal consumption expenditure (PCE) indicator, which the Federal Reserve attaches more importance to, will release the latest data on May 31. In today's speech, Powell predicted that the indicator would rise by about 2.2%.

Wall Street analysts generally expect that the price increase trend driven by tariffs will become more obvious in the coming months, which makes the Federal Reserve hesitant to cut interest rates.

Michael Hansen, an economist at JPMorgan Chase, pointed out that tariffs may cause a surge in US commodity prices in June and July, which makes the Federal Reserve more cautious when considering cutting interest rates. Due to the uncertainty and volatility brought by the tariff policy during the Trump administration, the Federal Reserve is taking a wait-and-see approach to assess the specific impact of the final policy implementation on the economy.

The following is the full text of the speech:

Good morning. It is a pleasure to welcome everyone to today's meeting. Thomas Laubach's research and support for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) have helped us better understand monetary policy, and it is very appropriate to continue this work in his name today. Thank you to the authors of the paper, the discussion guests and the panel participants, and thank you to Trevor and his team for organizing this meeting, and everyone's efforts have brought us together.

Like the last review, the 2025 review will have three key components: this meeting, “Fed Listens” events held at the Federal Reserve Banks, and discussions and deliberations among policymakers at FOMC meetings (supported by staff analysis). In the current review, we will revisit certain aspects of the strategic framework in light of the past five years and consider enhancing the Committee’s policy communication tools, including language on forecasts, uncertainties, and risks.

Consensus Statement

In 2012, the FOMC first codified its monetary policy framework in a document called the Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, which we call the “Consensus Statement.” The wording of the opening paragraph has never changed, articulating our commitment to fulfilling our congressional mandate and clearly explaining our actions and why (Figure 1).

Such clarity reduces uncertainty, improves policy effectiveness, and enhances transparency and accountability.

Then-Chairman Ben Bernanke led the Commission in developing the initial consensus statement, which adopted a 2 percent inflation target and outlined our approach to achieving the dual mandate given by Congress. The framework set forth in that document is generally consistent with best practices for flexible inflation-targeting central banks.

The structure of the economy evolves over time, and monetary policymakers’ strategies, tools, and communications need to adapt accordingly. The challenges of the Great Depression, the Great Inflation, and the Great Moderation were different, and today’s challenges are different again. Frameworks need to be adaptable to a wide range of conditions, but they also need to be updated regularly to reflect changes in the economy and our understanding of it.

2019-2020 Review

From 2012 to 2018, the FOMC voted to reaffirm the consensus statement at its January meeting, with no substantive changes in most years. In 2019, we changed that practice, conducted our first public review, and indicated that we would repeat such reviews approximately every five years. Five years is not a magic number, but we believe that this frequency is appropriate for reassessing the structural features of the economy and communicating with the public, practitioners, and academics about the performance of the framework.

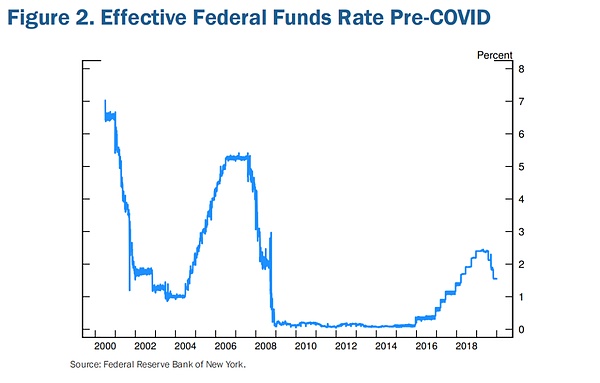

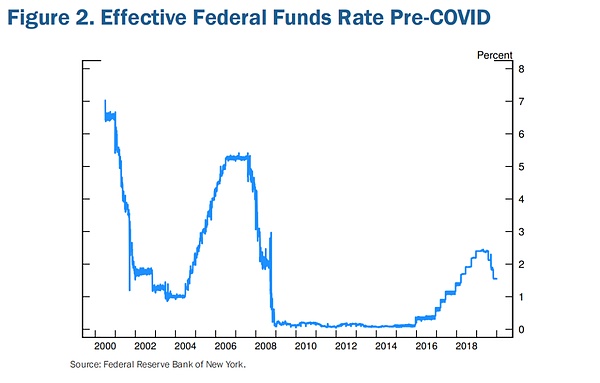

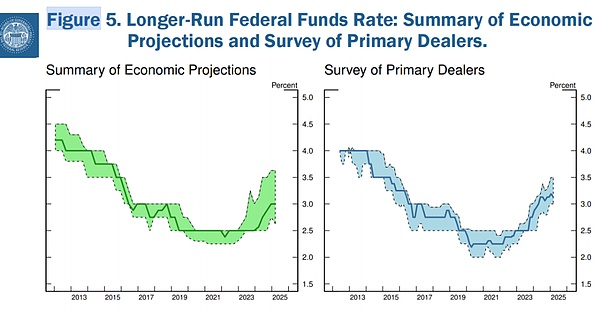

At the time of our last review, we had been living in the new normal for about a decade, characterized by low interest rates near the effective lower bound, low growth, low inflation, and a very flat Phillips curve. If there is one statistic that sums up that era, it is that the policy rate remained at the lower bound for seven years after the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis (Figure 2).

After starting to raise rates in December 2015, we were able to raise the policy rate only very slowly over three years to a peak of 2.4%. Seven months later, we began to cut rates, bringing them to 1.6% by the end of 2019 and keeping them there when the pandemic hit a few months later. Other major advanced economies had lower policy rates, many even negative, and inflation was persistently below target.

The view was that when the economy experienced even a mild recession again, we would return to the lower bound, possibly for a long time. The pain of the decade after the financial crisis has proven this point. Inflation can fall when the economy is weak, and with nominal interest rates fixed at zero, rising real interest rates would further depress employment growth and add downward pressure on inflation and inflation expectations.

Based on these concerns, we have pursued policy to compensate for persistent shortfalls from our inflation objective, an approach common in the broad literature on risks to the lower bound. Given the downside risks to employment and inflation from being close to the lower bound, and the need to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at 2 percent, we said that, following periods of inflation running persistently below 2 percent, we would likely aim for inflation to run just above 2 percent for some time.

We also concluded that policy decisions would be based on assessments of “shortfalls” rather than “deviations” from maximum employment. Adjustments to “shortfalls” are not a commitment to permanently abandon preemption or to ignore labor market tightness, but rather an indication that labor market tightness alone is insufficient to trigger a policy response unless the Committee judges that it would lead to unwelcome inflation pressures if left unchecked.

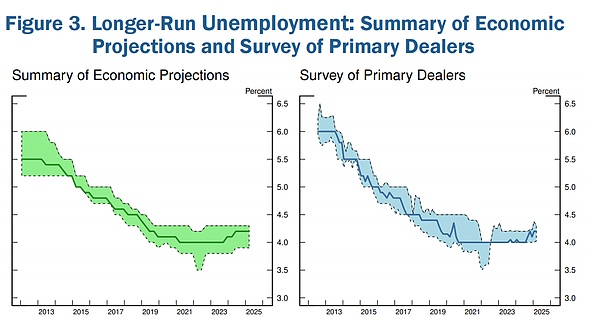

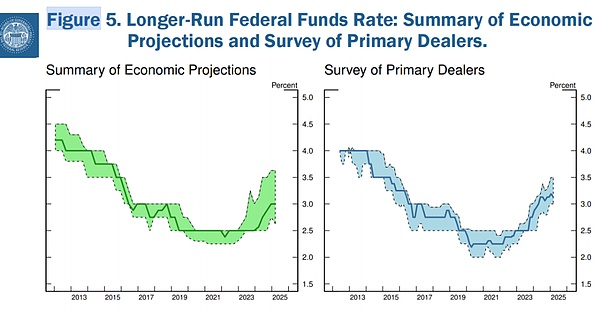

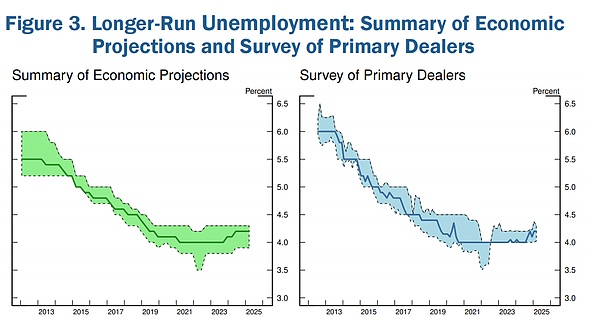

This adjustment reflects our experience in long expansions that have been characterized by historically low unemployment and low and stable inflation, suggesting that a policy approach that cautiously explores maximum employment can deliver the benefits of a strong labor market without endangering price stability. For example, in the years before the pandemic, unemployment was at multi-decade lows and inflation was below 2 percent. By December 2019, estimates of the longer-run unemployment rate had fallen substantially (Figure 3). The use of “undershoot” recognizes that the combination of low inflation and low unemployment does not necessarily constitute an unfavorable trade-off for monetary policy.

Current Assessment

In the current assessment, the Committee is discussing what we have learned from our experience over the past five years. We plan to complete specific revisions to the consensus statement in the coming months. We are paying particular attention to changes for 2020, considering discrete but important updates that reflect our new understanding of the economy, and the public's interpretation of those changes. During the discussion, participants saw a need to revisit the wording on "undershooting." We had similar views on the average inflation target at last week's meeting. We will ensure that the new consensus statement is responsive to the broad economic environment and changes.

In addition to revising the consensus statement, we will consider enhancing formal policy communications, particularly on forecasts and the role of uncertainty. In assessing the 2020 framework and policy decisions in recent years, a common observation is the need for clear communication of complex events as they unfold. Although academics and market participants generally agree that the FOMC's communication is effective, there is always room for improvement. Clear communication is a key issue even in relatively calm times. How to promote a broader understanding of the uncertainty that the economy generally faces is an important topic. In periods when shocks are larger, more frequent, or more diffuse, effective communication requires that we convey the uncertainty in our understanding of the economy and the outlook. We will examine how we can improve on this front.

Finally, thank you all again for being here. We look forward to the discussions over the next two days, which will help us broaden and deepen our thinking on these issues and will be critical to the success of our assessment.

Davin

Davin