Author: Daii Source: mirror But this time, the warning comes from Simon Johnson, a scholar who just won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2024. This means that his views carry sufficient weight in both academia and policy circles and cannot be ignored. Simon Johnson, formerly Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has long focused on global financial stability, crisis prevention, and institutional reform. In the fields of macro-finance and institutional economics, he is one of the few voices that can influence both academic consensus and policy design. In early August of this year, he published an article titled "The Crypto Crises Are Coming" on Project Syndicate, a globally renowned commentary platform. This platform, known as a "global thought leader's column," consistently provides contributions to over 500 media outlets in over 150 countries. Contributors include politicians, central bank governors, Nobel laureates, and leading scholars. In other words, the views expressed here often reach global decision-makers. In the article, Johnson took aim at a series of recent crypto legislation in the United States, particularly the recently passed GENIUS Act and the ongoing CLARITY Act. In his view, these bills, while ostensibly intended to establish a regulatory framework for digital assets like stablecoins, effectively relax key constraints in the name of legislation. (Project Syndicate) He bluntly stated: Unfortunately, the crypto industry has acquired so much political power – primarily through political donations – that the GENIUS Act and the CLARITY Act have been designed to prevent reasonable regulation. The result will most likely be a boom-bust cycle of epic proportions. At the end of the article, he offers a cautionary conclusion: The US may well become the crypto capital of the world and, under its emerging legislative framework, a few rich people will surely get richer. But in its eagerness to do the crypto industry's bidding, Congress has exposed Americans and the world to the real possibility of the return of financial panics and severe economic damage, implying massive job losses and wealth destruction. So, how does Johnson construct his arguments and logical chain? Why does he reach such a conclusion? This is exactly what we're going to unpack next. 1. Is Johnson's warning justified? Johnson first laid out the overall context: the GENIUS Act was officially signed into law on July 18, 2025, and the CLARITY Act passed the House of Representatives on July 17 and awaits Senate deliberation. These two bills, for the first time at the federal level, clarify what a stablecoin is, who can issue it, who regulates it, and within what scope it operates. This effectively paves the way for crypto activities to expand in scale and reach new audiences. (Congress Network) Johnson's subsequent risk deductions were based precisely on this "institutional combination punch." 1.1 Interest Rate Spread: The Profit Engine for Stablecoin Issuers His first step was to grasp the central question of "where the money comes from"—stablecoins are zero-interest liabilities for holders (holding one USDC does not generate interest); issuers, on the other hand, invest their reserves in a yield-generating asset pool, profiting from the interest rate spread. This isn't speculation; it's a fact clearly stated in both the terms and financial statements:

USDC's terms and conditions clearly state: "Circle may deploy reserves in interest-bearing or other yield-earning instruments; these returns do not accrue to holders." (Circle)

Media and financial disclosures further confirm that Circle's revenue relies almost entirely on interest on reserves (nearly all of its revenue in 2024 will come from this item), and that interest rate fluctuations significantly impact profitability. This means that as long as regulations allow and repayment expectations are not compromised, issuers have a natural incentive to maximize returns on their assets. (Reuters, The Wall Street Journal)

In Johnson's view, this "interest rate drive" is structural and normalized—when the core of profits comes from maturity and risk compensation, and when returns are not shared with holders, the impulse to "chase higher-yielding assets" must be regulated.

The problem is that the boundaries of these rules are inherently flexible.

1.2 Rules: The devil is in the details

He then analyzed the micro-provisions of the GENIUS Act, pointing out several seemingly technical details that may rewrite the system dynamics in times of stress:

Whitelist reserves: Article 4 requires a 1:1 reserve ratio, which is limited to cash/central bank deposits, protected deposits, US Treasury bonds with a term of ≤ 93 days, (reverse) repos, and government money market funds (government MMFs) that invest only in the above assets. While appearing robust, it still allows for certain maturities and repurchase structures—which, in times of stress, may mean having to sell bonds to redeem. (Congress Network) The bill authorizes regulators to set capital, liquidity, and risk management standards, but explicitly requires that these standards "do not exceed… sufficient to ensure the issuer's ongoing operations." Johnson believes this reduces the safety margin to a "minimum sufficient" level, rather than providing redundancy for extreme situations. (Congress Network) He argues that while whitelists and minimum requirements make the system more efficient in normal circumstances, maturities and repurchase chains can amplify the time lag between redemption and liquidation, as well as price shocks, in extreme situations. 1.3 Speed: Bankruptcy is measured in minutes. Third, he put "time" on the table. While the GENIUS Act codifies the priority of repayment for stablecoin holders in bankruptcy and requires courts to strive to enter distribution orders within 14 days, appearing investor-friendly, it is still too slow compared to the minute-by-minute redemption speed on the chain. (Congress Network) Real-world examples confirm this speed mismatch: During the SVB (Silicon Valley Bank) incident in March 2023, USDC plummeted to $0.87–0.88, only to stabilize by filling the gap and resuming redemptions. Research from the New York Fed documented a pattern of "collective runs" and "flights to safety" on stablecoins in May 2022. In other words, panic and redemptions occur on an hourly basis, while laws and courts operate on a daily basis. (CoinDesk, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics) This is precisely what Johnson calls the system's "leverage point": when the asset side must respond to minute-by-minute debt flight by selling bonds, any procedural delay can amplify individual risks into systemic shocks. He then discussed the cross-border dimension: The GENIUS Act allows foreign issuers under comparable regulations to sell in the US and requires them to maintain sufficient liquidity in the US, but the Treasury Department can waive some of these requirements through mutual recognition arrangements. Although the Act does not directly state that investments in non-US dollar sovereign bonds are permitted, Johnson is concerned that "comparable" does not mean "equivalent," and that the relaxation of mutual recognition and reserve locations could allow some reserves to be unpegged from the US dollar, thereby amplifying exchange rate mismatch risks if the US dollar appreciates significantly. (Congressional Network, Gibson Dunn, Sidley Austin) Meanwhile, the bill leaves ample room for state-qualified issuers and requires federal intervention to meet certain conditions, creating fertile ground for regulatory arbitrage—issuers will naturally migrate to jurisdictions with the least stringent regulations. (Congressional Network) The conclusion is: when the patchwork of cross-border and interstate regulations is combined with the profit motive, risks tend to be pushed to the softest edges. 1.5 Fatal Flaw: No "Lender of Last Resort" and Loose Political Constraints In terms of institutional design, the GENIUS Act does not establish a "lender of last resort" or insurance backstop for stablecoins. While excluding stablecoins from the definition of commodities, the bill also does not include them in the category of insured deposits—to do so, issuers must qualify as insured depository institutions. As early as 2021, the President's Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) recommended that only insured depository institutions be allowed to issue stablecoins to mitigate bank run risks, but this recommendation was not adopted in the bill. This means that stablecoin issuers lack FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) insurance and cannot access discount window support in a crisis, creating a significant gap with the traditional "bank-style prudential framework." (Congress website, U.S. Department of the Treasury) Johnson is even more concerned about the potential for the political and economic context to perpetuate this institutional gap. In recent years, the influence of the crypto industry in Washington has rapidly increased. Super PACs (Super Political Action Committees) such as Fairshake alone raised over $260 million in the 2023-24 election cycle, becoming one of the most vocal donors. The industry's external fundraising for congressional elections has even reached the billion-dollar mark. Under this situation, the "flexible choice" in the law and political motivations may reinforce each other, making the "minimum sufficient" safety cushion not only a realistic option, but also likely to evolve into a long-term norm. (OpenSecrets, Reuters) 1.6 Logic: From Legislation to Depression Putting the above links together, we have Johnson’s reasoning path: A. Legislation justifies larger-scale stablecoin activities → B. Issuers rely on a profit model of zero-interest liabilities and interest-bearing assets → C. The law chooses "minimum sufficient" for reserve requirements and regulatory standards, while retaining the flexibility of arbitrage and mutual recognition.

→ D. During a bank run, minute-by-minute redemptions are met with day-by-day disposals, forcing sellers to repay bonds, impacting short-term interest rates and the repo market.

→ E. If combined with foreign currency exposure or the widest regulatory boundaries, the risk is further amplified.

→ F. The lack of a lender of last resort and insurance guarantees makes individual imbalances easily evolve into industry fluctuations.

This logic is convincing because it combines a detailed reading of the law (such as "do not exceed... ongoing operations" and "14-day distribution order") with empirical facts (USDC fell to 0.87-0.88, and the collective redemption of stablecoins in 2022), and is consistent with the FSB (Financial Stability Board) Since 2021, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the BIS (Bank for International Settlements), and the PWG have all shown a strong convergence in their focus on bank runs and fire sales. (Congress Network, CoinDesk, Liberty Street Economics, Financial Stability Board) 1.7 Summary Johnson doesn't assert that stablecoins will inevitably trigger a systemic crisis. Instead, he warns that when "interest rate differential incentives + minimum safety cushions + regulatory arbitrage/mutual recognition flexibility + delayed resolution speeds + the absence of LLRs (Lender of Last Resorts)/insurance" combine, institutional flexibility can become a risk amplifier. In his view, some of the institutional choices in "GENIUS/CLARITY" make it more likely that these conditions will coexist, hence the boom-bust warning. Two historical crises involving stablecoins also seem to indirectly validate his concerns. 2. The "Moment of Truth" of Risk If Johnson's previous analysis is about "institutional concerns," then the true test of the system is when a run occurs—the market provides no warning and ample time to react. These two distinct historical events provide a clear glimpse into the potential vulnerability of stablecoins under pressure.

2.1 Bank Run Mechanics

Let’s first look at UST in its “barbaric era.”

In May 2022, the algorithmic stablecoin UST quickly lost its anchor within a few days, and the related token LUNA entered a death spiral. The Terra chain was forced to shut down, and exchanges successively delisted it. The entire system evaporated approximately US$40-45 billion in market value within a week, triggering a wider wave of crypto sell-offs. This wasn't just any price fluctuation, but a classic bank run: when the promise of "stability" relies on a cycle of minting and selling within the protocol, rather than on quickly redeemable external, highly liquid assets, once that confidence shatters, selling pressure will self-amplify until the system completely collapses. (Reuters, The Guardian, Wikipedia) Looking back at the USDC unpegging incident, which occurred before the "compliance era," it reveals how off-chain banking risks can be instantly transmitted to the on-chain. In March 2023, Circle disclosed that it had approximately $3.3 billion in reserves held at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which was experiencing a sudden liquidity crisis. Within 48 hours of the announcement, USDC's secondary market price plummeted to as low as $0.88. It wasn't until regulators announced full protection for SVB deposits and launched the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program) emergency tool that market expectations quickly reversed and the peg was restored. That week, Circle reported $3.8 billion in net redemptions; third-party statistics show that on-chain burns and redemptions continued to increase over the next few days, with a peak single-day redemption nearing $740 million. This demonstrates that even if reserves are primarily invested in highly liquid assets, as long as the "redeem path" or "bank custody" are questioned, a run can unfold in minutes or hours until a clear liquidity backstop emerges. (Reuters, Investopedia, Circle, Bloomberg.com)

Looking at the two events side by side, you will find that the same set of "bank run mechanics" can be triggered in two ways:

UST: The endogenous mechanism is fragile - there is no verifiable and quickly liquidated external asset anchor, and it relies entirely on expectations and arbitrage cycles;

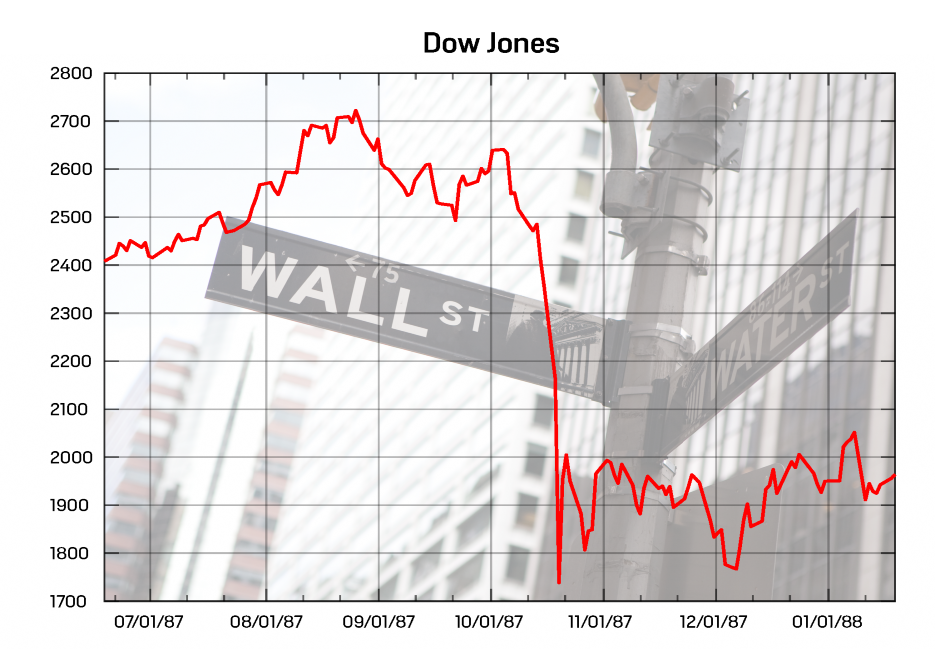

USDC: Although the external anchor exists, the off-chain supporting point is unstable - the single point failure on the bank side is instantly amplified on the chain into a price and liquidity shock. 2.2 Action and Feedback The New York Fed team used the framework of money market funds to describe this behavior: stablecoins have a clear threshold of "breaking $1." Once this threshold is broken, redemptions and rotations accelerate, and a flight to safety from "riskier stablecoins" to "perceived safer stablecoins" occurs. This explains why, when USDC depegged, some funds simultaneously flowed into "Treasury bonds" or perceived more stable alternatives—the migration was rapid, clear, and self-stimulating. (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Liberty Street Economics) Even more noteworthy is the feedback loop: when on-chain redemptions accelerate and issuers need to sell bonds to cover their losses, selling pressure is directly transmitted to the short-term Treasury bond and repo markets. A recent BIS working paper, using daily data from 2021–2025, found that a significant inflow of stablecoin funds would lower the three-month Treasury yield by 2–2.5 basis points within 10 days; while a similar outflow would have an even stronger upward yield effect, 2–3 times that of the former. In other words, the procyclical and countercyclical fluctuations of stablecoins have already left a statistically identifiable "fingerprint" on traditional safe-haven assets. If a large, short-term redemption, similar to USDC, were to occur, the "passive sell-off-to-price shock" transmission path would be a real possibility. (Bank for International Settlements) 2.3 Lessons Learned The cases of UST and USDC are not isolated incidents, but rather two structural warnings: "Stability" without the backing of redeemable external assets is essentially a race against coordinated behavior; even with high-quality reserves, the vulnerability of a single point in the redemption path is instantly amplified on-chain; the time lag between the speed of a run and the speed of its resolution determines whether a run will evolve from a localized risk into a systemic disturbance. This is why Johnson discussed "stablecoin legislation" and "bank run mechanics" together—if legislation only provides a minimum safety cushion but fails to incorporate intraday liquidity, redemption SLAs (Service Level Agreements), stress scenarios, and orderly resolution into enforceable mechanisms, then the next "moment of truth" may come even sooner. So the question isn't "is the legislation wrong?" but rather, it's about acknowledging that: proactive legislation is clearly better than no legislation, but reactive legislation may be the true coming-of-age ceremony for stablecoins. 3. Stablecoins' Coming of Age: Reactive Legislation If the financial system is likened to a highway, proactive legislation is like painting guardrails, speed limit signs, and emergency escape strips before driving. Reactive legislation often occurs after an accident, filling in gaps with thicker concrete piers. To explain the "coming of age ceremony for stablecoins," the best reference is the history of the stock market. 3.1 The Coming of Age of Stocks The U.S. securities market didn't always have disclosure systems, exchange rules, information asymmetry, and investor protection. These "guardrails" were almost entirely erected after the crash. The 1929 stock market crash plunged the Dow Jones Industrial Average into the abyss, sending banks into bankruptcy, reaching a peak in 1933. It was only after this disaster that the United States passed the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, codifying information disclosure and ongoing oversight and establishing the SEC as a permanent regulatory body. In other words, the stock market matured not through persuasive ideas but through the shaping of crises—its "coming of age" was a passive legislation enacted after the crisis. (federalreservehistory.org, Securities and Exchange Commission, guides.loc.gov)

1987's "Black Monday" remains another collective memory: the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted 22.6% in a single day. Only then did US exchanges institutionalize the "circuit breaker mechanism," providing the market with a brake and an emergency hedge. During extreme moments like 2001, 2008, and 2020, circuit breakers became a standard tool for curbing stampedes. This is a classic example of passive regularization—first comes the pain, then the system. (federalreservehistory.org, Schwab Brokerage) 3.2 Stablecoins Stablecoins, like stocks, are not "secondary innovations" but rather, like stocks, infrastructure innovations. Stocks transform "ownership" into tradable certificates, reshaping capital formation; stablecoins transform "fiat cash" into programmable, globally settled 24/7 digital objects, reshaping payment and clearing. The latest BIS report bluntly states that stablecoins have been designed as a gateway into the crypto ecosystem, serving as a medium of exchange on public blockchains and gradually becoming deeply integrated with traditional finance—this is already a reality, not just a concept. (Bank for International Settlements) This "real-virtual" integration is taking shape. This year, Stripe announced that Shopify merchants can now accept payments in USDC, with the option of automatic settlement to their local currency accounts or direct retention in USDC. This on-chain cash leg connects directly to merchant ledgers. Visa also clearly defines stablecoins on its stablecoin page as a payment vehicle that combines the "stability of fiat currency with the speed of crypto," integrating tokenization and on-chain finance into the payment network. This means that stablecoins have become integrated into real-world cash flows. When the cash leg is on-chain, the risks are no longer limited to the crypto world. (Stripe, Visa Corporate) 3.3 The inevitable rite of passage From a policy perspective, why is “passive legislation” for stablecoins almost inevitable? Because it possesses classic "gray rhino" characteristics:

Significant scale: On-chain stablecoin settlement and activity have become a sidechain for global payments, sufficient to generate spillover effects in the event of a failure;

Increased coupling: BIS measurements show that large outflows of stablecoin funds significantly push up 3-month US Treasury yields by 2–3 times the magnitude of equivalent inflows, indicating that it has affected the short-end pricing of public security assets;

Samples have appeared: Two "bank runs" on UST and USDC demonstrate that minute-by-minute panic can penetrate both on-chain and off-chain.

This is not a random coincidence of a black swan, but a repeatable mechanic. Once the first large-scale spillover occurs, policies will inevitably strengthen guardrails—much like the stock market in 1933/1934 and the circuit breakers in 1987. (Bank for International Settlements) Therefore, "passive legislation" is not a denial of innovation; on the contrary, it is a sign of innovation being socially accepted. When stablecoins truly combine the speed of the internet with the unit of account of central bank currency, they will be upgraded from a "circle tool" to a "candidate for a public settlement layer." Once it enters the public layer, society will, after an incident, impose stricter rules requiring it to possess the same, or even higher, liquidity organization and orderly disposal capabilities as money market funds: Circuit breakers (swing pricing/liquidity fees); Intraday liquidity red lines; Redemption SLAs; Cross-border equivalent supervision; Minute-by-minute triggering of bankruptcy priority; These paths mirror the path taken by the stock market: first letting go to allow efficiency to fully manifest, then using crises to tighten the guardrails. This is not a step backward, but a rite of passage for stablecoins. If the stock market's coming-of-age ceremony was the bloody storm of 1929, when the three-piece set of "disclosure, regulation, and law enforcement" was nailed into the system, then the coming-of-age ceremony for stablecoins is the three-piece set of "transparency, redemption, and disposal" truly enshrined in code and law. None of us wants to see a repeat of the tragedy of the crypto crisis, but the greatest irony of history is that humanity has never truly learned its lesson. Innovation has never been crowned by slogans, but rather by constraints. Verifiable transparency, enforceable redemption commitments, and predictable, orderly disposal are the ticket for stablecoins to become part of the public settlement layer. If a crisis is unavoidable, let it arrive sooner rather than later, exposing vulnerabilities and allowing timely repairs to the system. This way, prosperity will not end in collapse, nor will innovation be buried in the ruins. Terminology Quick Overview: Redemption is the process by which holders redeem stablecoins for fiat currency or equivalent assets at face value. The speed and path of redemption determine whether a bank can survive a run. Reserves: The pool of assets (cash, central bank/commercial bank deposits, short-term US Treasury bonds, (reverse) repos, government money market funds, etc.) held by issuers to guarantee repayment. Their composition and maturity determine liquidity resilience. Spread: Stablecoins are zero-interest liabilities to holders; issuers invest their reserves in interest-bearing assets to earn a spread. Spreads naturally incentivize allocations to higher yields and longer maturities. (Reverse) Repos: Short-term financing/investment arrangements collateralized by bonds. Government Money Market Funds (Government MMFs) are money market funds that hold only highly liquid government assets. They are often considered part of "cash equivalents," but can also face redemption pressure in extreme circumstances. Insured deposits: Bank deposits covered by deposit insurance (e.g., FDIC). Deposits held by non-bank stablecoin issuers generally do not enjoy the same protection. Lender of Last Resort (LLR): A public backstop that provides liquidity in a crisis (e.g., a central bank discount window/special facility). In its absence, individual liquidity shocks are more likely to escalate into systemic sell-offs. Fire sales: A chain reaction of price overshoots caused by the forced rapid sale of assets, often seen in bank runs and margin calls. "Breaking the Buck": An instrument nominally pegged to $1 (e.g., MMFs/stablecoins) experiences a price deviation below par, triggering a chain reaction of redemptions and flight to safety. Intraday liquidity refers to the ability to access/liquidate cash and equivalents within the same trading day. It determines whether "minute-level liabilities" can be matched with "minute-level assets." Service Level Agreements (SLAs), which explicitly state commitments on redemption speed, limits, and responsiveness (such as "T+0 redemption limits" and "queuing mechanisms"), help stabilize expectations. Orderly Resolution refers to the distribution and liquidation of assets and liabilities according to a pre-planned plan in the event of default or bankruptcy, to avoid disorderly distribution. Cross-border Equivalence/Recognition refers to the recognition of equivalence in regulatory frameworks across jurisdictions. If "equivalence ≠ equivalence" is true, regulatory arbitrage is likely to occur.

Safety cushion / Buffer: Redundancy in capital, liquidity, and duration to absorb pressure and uncertainty. A "minimum sufficient" that is too low will fail in extreme moments.

Weiliang

Weiliang

Weiliang

Weiliang Anais

Anais Catherine

Catherine Joy

Joy Kikyo

Kikyo Miyuki

Miyuki Weatherly

Weatherly Catherine

Catherine Kikyo

Kikyo Alex

Alex