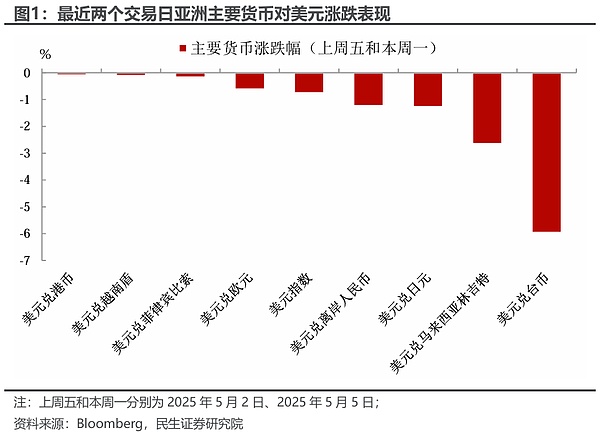

In recent days, the Asian foreign exchange market has fluctuated violently. The onshore RMB has risen by nearly 600 points, the offshore RMB has once risen above 7.20, the Hong Kong dollar has continuously touched the strong side exchange guarantee, and the Taiwan dollar has soared to a "historical level", with a cumulative increase of more than 9% in two days, which is very rare in the foreign exchange market.

Behind the surge, in addition to the most direct trigger being the positive signal of the US tariff negotiations, the market is hotly discussing that a behind-the-scenes version of the "Mar-a-Lago Agreement" is brewing.

According to the trading desk, despite market rumors, JPMorgan Chase believes in its latest foreign exchange strategy weekly report that the weakness of the US dollar is not due to a coordinated agreement, but is driven by many changes such as fundamentals.

For example, US economic growth expectations have been lowered, and concerns about stagflation caused by trade conflicts have intensified; the independence of the Federal Reserve has caused controversy; the rise in the US term premium and the decline in the Federal Reserve's terminal interest rate have occurred at the same time; Germany's fiscal policy has turned to easing, which has supported the European capital market.

Against this background, the attractiveness of US dollar assets has declined, and funds have naturally flowed to other markets.

In addition, JPMorgan Chase said that the market generally believes that there is another powerful driving force behind the strong Asian currencies - the huge amount of US dollar assets accumulated over many years of trade surpluses have begun to flow back, which has created strong foreign exchange hedging pressure.

Goldman Sachs analyst Teresa Alves believes that the US dollar is overvalued by 16%. If there are "significant changes" in the macro fundamentals, it may adjust quickly or even overshoot.

Why is the market so convinced that there is an agreement?

The "Mar-a-Lago Agreement" originally refers to Trump's strategy of lowering the US dollar and boosting the currencies of exporting countries through multilateral means. Although the idea has never been officially implemented, the recent abnormal fluctuations in Asian currencies have once again rekindled this topic.

For example, the South Korean Finance Minister recently admitted that he would hold "working-level consultations" with the US Treasury Department on the exchange rate issue; and the "Central Bank" of Taiwan, China, issued a statement after the appreciation of the New Taiwan Dollar, saying that it was "not under pressure from the United States." These vague responses have increased the market's speculation space.

More importantly, the market generally believes that this round of exchange rate market is "unusual." JPMorgan Chase pointed out that a surge like the New Taiwan Dollar is almost impossible to happen without policy acquiescence. The foreign exchange markets of Asian countries have long been dominated by regulatory authorities, so the saying "there is no wind without waves" is not groundless in this context.

And unlike the Plaza Accord in 1985, Asian countries (especially export-oriented economies) currently have accumulated a large amount of US dollar assets. In this case, the government does not need to intervene directly by selling US dollars. It can promote currency appreciation by increasing the hedging ratio of enterprises or requiring them to convert part of their US dollar income into local currency through "window guidance."

Experts at BNP Paribas said:

While no economy will officially admit that currency valuation is a focus of negotiations, market expectations indicate otherwise. This is particularly noteworthy given that the Mar-a-Lago agreement emphasizes that the overvaluation of the dollar is the root cause of the US trade imbalance.

Although there is still no official conclusion on whether the "Mar-a-Lago agreement" exists, the rise of Asian currencies has already caused ripples in the capital market. Under the intertwined influence of geopolitics, macroeconomic policies and market expectations, an invisible "currency storm" may be forming.

Asia's huge dollar assets become a key variable

The market generally believes that there is another powerful driving force behind Asia's strong currencies - the huge dollar assets accumulated over many years of trade surpluses have begun to flow back.

According to JPMorgan Chase estimates, Chinese exporters alone hold $400 billion to $700 billion in assets, plus the net international investment position surpluses of other Asian exporters, which constitutes a huge potential repatriation and foreign exchange hedging pressure.

UBS's research on the 5th also pointed out that in addition to stock inflows, the main drivers of this round of New Taiwan dollar appreciation are exchange rate hedging by insurance companies, enterprises, etc. and the stop loss of previous New Taiwan dollar financing arbitrage transactions.

In addition, China's recent reduction in the fixed exchange rate between the US dollar and the RMB is also seen as an important policy signal, clearing the way for the widespread appreciation of Asian currencies.

Goldman Sachs estimates: The US dollar is overvalued by 16%

The depreciation of the US dollar may not be over yet?

Goldman Sachs analyst Teresa Alves said in a report on May 1 that the US dollar is currently overvalued by about 16%, and this valuation mismatch is mainly driven by global funds chasing the superior return prospects of the United States.

As the US return advantage gradually weakens, the overvaluation of the US dollar may gradually correct.

Goldman Sachs research pointed out that the degree of overvaluation of the US dollar is highly dependent on the assumption of the "standard level" of the current account.

The current actual current account deficit of the United States is about 4%. If the current account deficit is reduced to 2.6%, it will correspond to a US dollar adjustment of about 16.5%; if it is further reduced to 2% (close to the IMF's 2023 standard value), it may lead to a 22% depreciation of the US dollar; if it is reduced to 1%, it may require a 31% depreciation of the US dollar to achieve.

Investors should pay attention to the changing trends of the US current account and global capital flows, and prepare for possible adjustments to the US dollar.

Clement

Clement

Clement

Clement Catherine

Catherine Hui Xin

Hui Xin Clement

Clement Brian

Brian Aaron

Aaron Jixu

Jixu Jasper

Jasper Clement

Clement Kikyo

Kikyo