Translated by: Liu Jiaolian

Jiaolian Note: Before and after the FOMC meeting of the Federal Reserve in September, which exceeded expectations by cutting interest rates by 50bp, many self-media, experts, and financial advisors jumped out to sing the praises of bonds and encouraged everyone to rush into US bonds. At that time, they came up with a perfect financial common sense: when interest rates go down, bond yields will fall and bond prices will rise. Jiaolian has repeatedly reminded in internal references and articles to pay attention to "counter-common sense" situations, but we still hear and see many unfortunate cases. When the Federal Reserve decided to cut interest rates on September 18, the 10-year US Treasury yield was 3705bp; today, more than a month later, it has soared to 4224bp. In other words, rushing into US bonds has lost more than 12% - for bonds, which are generally considered to be relatively low-risk investment products, a loss of more than 10% in a month is not a small amount. If you use leverage, the feeling will only be more sour. A sentence that has been tried and tested: A certainty is a 100% opportunity to make money, and there is a high probability that it will lose money. If something is bound to make money, then you may not even know there is such an opportunity. And if the pie in the sky is delivered to your mouth by a financial advisor, it is likely to be poisoned. Below, Jiaolian compiled a post by netizen Porter Standsberry to reveal the truth behind the Fed's rate cut and the abnormal surge in U.S. Treasury yields.

"Everyone has a plan until they get punched."

This is the situation faced by Jerome Powell (Jiaolian Note: Current Federal Reserve Chairman) as the bond market fights back against the Fed's best-laid plans to lower borrowing costs.

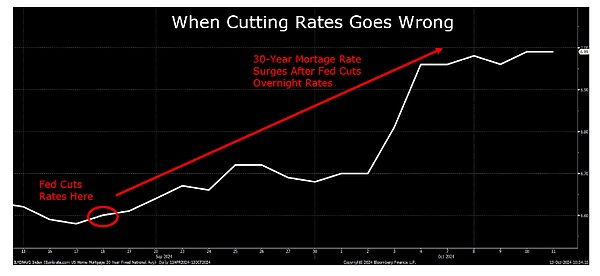

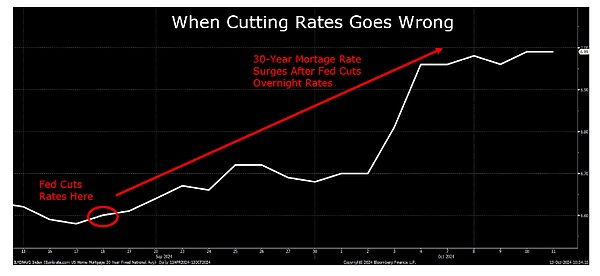

After Powell cut the overnight rate by 50 basis points on September 18, the yields on long-term bonds such as the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond did the opposite and soared 50 basis points.

This should not have happened...

Under normal circumstances, when the Fed is in step with the market, long-term borrowing costs follow the overnight rate set by the Fed. But when the Fed makes policy mistakes—like cutting rates before a presidential election despite high inflation—the market fights back.

We’ve seen this before, and spoiler alert: it doesn’t end well.

In 1971, even though inflation was above 4%, Fed Chairman Arthur Burns cut rates to improve Nixon’s political prospects in the 1972 presidential election.

Cutting rates amid high inflation allowed price pressures to become entrenched in the U.S. economy. American workers, fearing that rising prices would erode their wages, began demanding higher salaries.

This led to a self-reinforcing wage-price spiral that brought a decade of double-digit inflation, destructive interest rates, and stagnant economic growth: a toxic combination known as “stagflation.”

To finally curb inflation, the Volcker-era Fed raised the overnight interest rate to 20%.

But during this period, U.S. investors experienced a “lost decade,” with negative real returns on stocks and bonds.

The S&P 500 was trading at the same price level in 1979 as it was in 1968… and factoring in rampant inflation of over 50%, stock investors lost half their money in real returns.

Bond investors fared no better, with the 10-year Treasury losing 3% per year in inflation-adjusted terms, a loss of purchasing power of about 30% over the decade.

This was the worst decade for investor returns since the Great Depression.

In this post, I’ll explain why all signs point to a repeat of this in the future.

Unlike stocks, which tend to temporarily defy economic gravity during periods of extreme optimism (like today), the bond market is much more rigid. For fixed-income investors, inflation is enemy number one—the silent thief capable of turning positive nominal interest rates into negative real (inflation-adjusted) returns.

Jerome Powell has fueled fears of entrenched inflation by cutting short-term interest rates too soon, repeating Arthur Burns’ fatal mistake as the Fed’s head, before taming consumer prices.

Bond investors remember the 1970s. Growing concerns about persistent inflation depressing real returns have them demanding a greater margin of safety now, causing long-term borrowing costs, such as the 10-year Treasury rate, to surge.

The 10-year Treasury is one of the world’s most important lending benchmarks, determining borrowing costs for a wide range of consumer and business loans. This includes the standard 30-year U.S. mortgage rate, which has been pushed higher by the 10-year Treasury, which surged 50 basis points after Powell’s recent rate cut.

This is a big problem because higher borrowing costs drive inflation even further. In the housing market in particular, high mortgage rates directly contribute to higher homeownership costs.

The monthly mortgage payment for an average-priced US home is now $2,215, meaning it now takes an annual household income of $106,000 to own an average home, compared to just $59,000 four years ago (2020).

Not surprisingly, housing costs were one of the biggest winners in the September inflation report, rising 4.9% year-over-year, far outpacing the overall inflation rate of 3.3%.

Meanwhile, the Fed’s rate cuts – which were supposed to support US economic growth – are also backfiring. Rather than reducing borrowing costs and boosting lending in the real economy, higher long-term interest rates are having the opposite effect.

We can see from the latest weekly data that new mortgage applications plummeted 17%. Mortgage refinancings fell even more, with last week’s figure falling a staggering 26%.

Higher borrowing costs aren’t the only factor contributing to stubborn inflation. Insurance is another major culprit, with costs generally rising at a faster rate than the overall CPI.

For nearly every American adult, insurance is a major cost of living and is often required by law. Imagine filing your taxes without reporting health insurance, applying for a mortgage without homeowners insurance, or driving without auto insurance.

Insurance companies suffered major profit losses in the early days of post-pandemic inflation because they had previously priced policies based on historical inflation rates of 1-2%. So when inflation spiked and claims far exceeded expectations, they had to take big losses.

Now, insurers are starting to recoup their losses from policyholders.

Insurance companies have made up for the losses with big price increases on new policies as old policies expired over the past few years. For example, employer-sponsored health plans are expected to see a 7% cost increase for the second year in a row—about twice the current CPI inflation rate. That’s the fastest increase in more than a decade, and has increased the average family’s health insurance premium by $3,000 in the past two years alone.

Meanwhile, premiums for home and auto insurance are rising at double-digit rates, as those who recently renewed their policies have felt all too well. With two consecutive devastating hurricanes expected to inflict huge losses on insurers, the industry will raise rates further to make up for those losses.

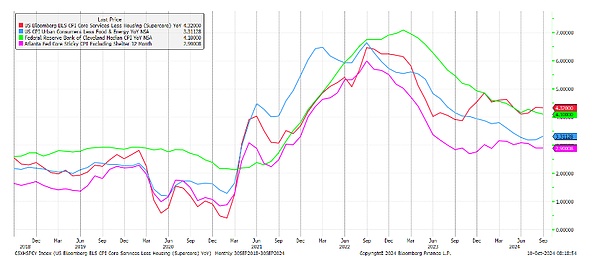

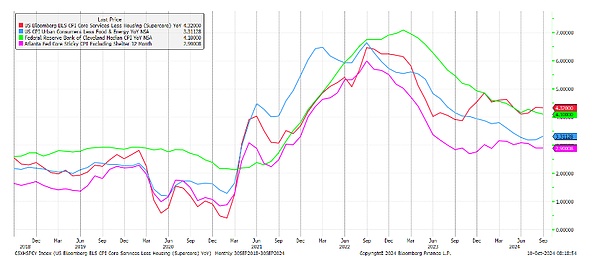

These and other stubborn costs are why—even stripping out volatile food and energy prices, the Fed’s various “core inflation” measures have remained stubbornly above 3% since the last time the CPI was below 2%. And if you analyze the median price in the CPI basket, inflation has also remained stubbornly around 4%.

Notably, this is also the inflation floor that the Fed was unable to break during the stagflation of the 1970s.

Despite the best efforts of politicians and media figures to fool consumers into thinking that inflation has been defeated, Americans living in the real world are still feeling the erosion of their wages by soaring prices.

Now, American workers are demanding ever-increasing wages to combat the cost-of-living crisis.

For example, 32,000 Boeing factory workers recently went on strike after their demands for a 40% wage increase over four years were unsuccessful. They ended the strike after Boeing agreed to a 35% wage increase over the next four years, equivalent to an annual increase of nearly 9%.

Meanwhile, the International Longshoremen’s Association ended its latest strike earlier this month after the employer agreed to a 62% wage increase over the next six years, bringing the average hourly wage to $63.

With wage increases like these setting the standard, it’s clear that inflation is taking root in the U.S. economy, fueling the flames of a wage-price spiral like the 1970s.

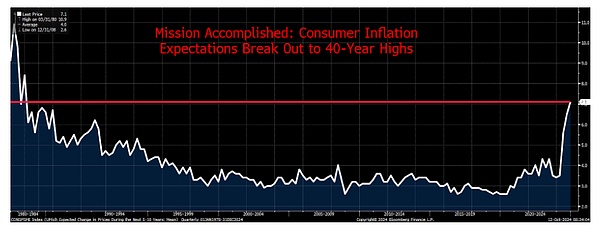

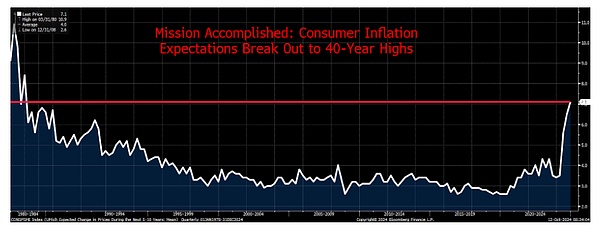

The chart below, which will soon become a nightmare for the Fed, shows that consumers’ inflation expectations have soared to their highest level in the past 40 years.

How long can the Fed keep up its “mission accomplished” rate-cutting trick when consumers expect annual inflation to exceed 7% over the next five to ten years and continue to demand higher wages?

U.S. policymakers are repeating the mistakes of the 1970s. They have sown the seeds of a decade or more of stubborn inflation, rising borrowing costs, and a "lost decade" for the U.S. economy and financial asset prices.

But this time, it could be worse. The biggest problem is that the U.S.'s highly indebted economy can no longer afford the 20% interest rates that were needed to curb runaway inflation in the 1970s.

The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is as high as 120%, compared with 30% in the 1970s.

If the Fed simply kept interest rates at 5% and forced the U.S. government to finance all of its outstanding debt at that rate, annual interest payments would quickly approach $2 trillion. That's equivalent to 40% of the government's annual tax revenue. If interest rates rise to 10%, the federal government will be forced to choose between paying for Social Security and Medicare benefits and funding the military, neither of which it can afford.

And at 20% borrowing costs, America will officially be shut down for business. Uncle Sam will be paying more in interest each year than he generates in taxes.

That’s why all roads lead to chronic runaway inflation. With the U.S.’s unsustainable debt load, raising overnight borrowing rates alone to control inflation is no longer a viable option.

The U.S. federal government is rapidly heading toward bankruptcy, and policymakers won’t even admit it, let alone address it. An honest default and debt restructuring are clearly not viable options for politicians seeking reelection. So the only option left is a dishonest default through inflation.

But don’t just take my word for it, check out legendary trader Paul Tudor Jones, who just explained today:

“All roads lead to inflation. I own gold and Bitcoin, and zero fixed income. The way out of this [debt problem] is through inflation.”

More important than what they say is to watch what the world’s top investors are doing.

Watch out for Stanley Druckenmiller, who just made a massive short on long-term U.S. Treasuries. Watch out for Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway and Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater, who are dumping bank stocks like stale commodities.

This weekend I was told by several “keyboard finance gurus” that the problems I was warning about with Bank of America were “just a piece of cake.” I heard the same objections when I warned about the crises facing Fannie Mae, General Motors, and more recently Boeing.

These judgments don’t require genius, just balance sheet math. The same is true of banking today.

Bank of America is currently facing a wrecked bond portfolio with losses equal to half the value of its tangible equity. If long-term interest rates exceed 10%, Bank of America will go bankrupt.

Of course, you can hope that the monetary and fiscal authorities will prevent that from happening.

But, as they say, “hope” is not a strategy. [1]

1: Teaching link note: This sentence means that "hope" alone is not enough to deal with real problems or challenges. It emphasizes the powerlessness of hope, especially when facing serious economic and financial crises. Hope can inspire people, but it is not an effective method or strategy to solve problems. Truly effective strategies require concrete actions and plans, not just hoping that things will get better. Therefore, the author emphasizes here that relying on hope without taking practical measures is not feasible.

Kikyo

Kikyo