Author: Zack Pokorny Source: Galaxy Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

Introduction

The crypto industry is a hotbed of innovation and risk-taking, and even the most fantastic ideas can be supported as long as they have the potential to become a reality. In this process, both teams and investors face challenges. In the past 12 months, as the industry has begun to pay more attention to sustainability and real growth, these challenges have become more prominent:

For the team: How to cultivate a group of coin holders who really care about the project in the early stage and do not sell tokens when the market fluctuates, so as not to "cut off the food" for the project? In the fast-paced crypto world, how to stay agile, make correct decisions quickly and adjust direction in time?

For Investors: How to price an early-stage project with no revenue, no users, but freely tradable tokens? Traditional tools—such as discounted cash flow models, revenue multiples, comparable valuations—are difficult to apply in this context. Valuation ultimately becomes more like venture capital, based on the perception and belief of the product, team, and market potential.

These problems are not unique to the crypto industry, but the decentralized nature of blockchain organizations makes some novel solutions possible. For decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), the market-based governance model of Futarchy brings the following advantages:

provides builders with clear, economically supported signals, reducing the ambiguity of token holders' positions in decision-making;

reduces information asymmetry, thereby promoting the decentralization of DAO governance;

forms a belief-weighted "capital structure table" (equity structure table) through market forces, which continuously tilts towards the most accurate and most supportive project holders;

investors can directly express their support or opposition to a DAO decision by adjusting their positions based on market price signals.

This article explores the fundamental role of futarchy in investment and decision-making in highly subjective, freely tradable, early-stage projects from 0 to 1. While futarchy is being experimented with on Solana through MetaDAO’s series of futarchy DAOs and in Optimism’s grant allocation mechanism, this article focuses on its theoretical principles and governance structures rather than specific practices.

Futarchy Governance in a Holistic Perspective

Futarchy, the idea of governance through markets and economic signals, was first proposed by economist Robin Hanson in his 2000 working paper “Shall We Vote on Values, But Bet on Beliefs?” He first used the word "Futarchy" in his paper, combining "future" (referring to the futures market) with "-archy" (the Greek suffix for rule), meaning "ruled by the futures market." He came up with the term almost casually, saying on the second page: "I adopted this term for no particular reason."

In the context of DAOs, Futarchy achieves the same goal as traditional token voting governance - guiding strategic decisions, but the path is different. It separates the two processes of "setting goals" and "evaluating how to achieve them." In traditional DAO governance, users use tokens to vote proportionally (that is, "one coin, one vote"), expressing a mixture of their values and beliefs. That is, when voting on a proposal, users often express both the results they hope to achieve (such as launching a new feature) and their beliefs about whether a plan can achieve the goal. The proposal with the most votes is ultimately adopted.

Futarchy, on the other hand, allows people to vote to set goals based on their values, and then the prediction market (i.e. "betting") evaluates which plan is most likely to achieve these goals. The advantage of this structure is that it separates "setting goals" from "prediction effects" and guides decisions through the predictive power of financial markets (prices and transactions). Participants will invest real money to express their predictions, which greatly enhances the accuracy of the predictions and the rigor of the analysis, which is difficult to do with traditional voting systems that do not pay costs.

The actual operation process is as follows:

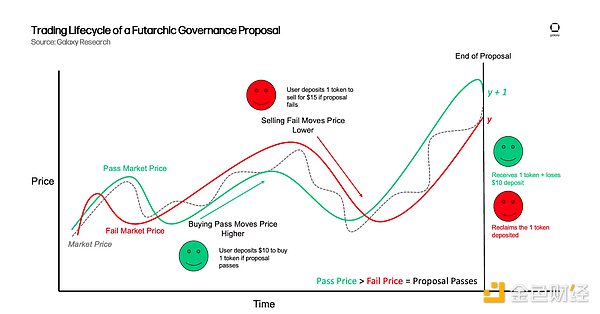

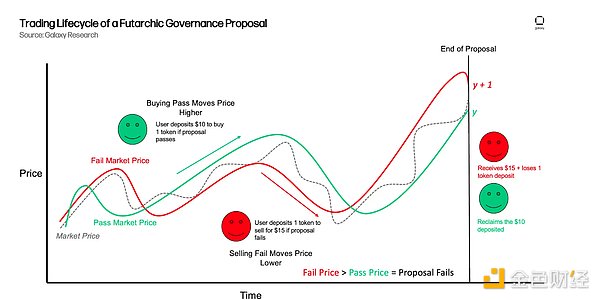

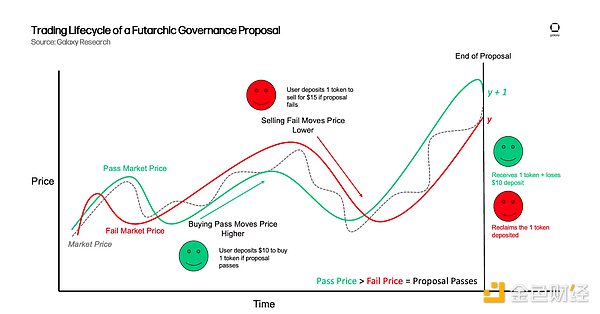

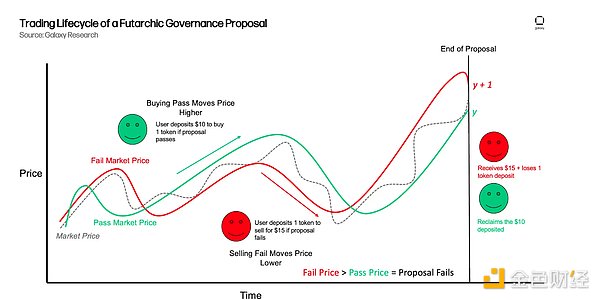

Each DAO proposal will generate two temporary token markets during the voting period: the pass market and the veto market, each denominated in US dollar stablecoins, giving different prices to the DAO token. These two markets are driven by independent automatic market makers (AMMs) and run in parallel with the main market (such as centralized exchanges and decentralized exchanges).

In these proposal markets, anyone can participate in transactions without being a token holder of the DAO. For example, even if you don't have the DAO's tokens, you can use stablecoins to buy in the proposal's "pass market" or "reject market."

During the voting period, the system will record the time-weighted average price (TWAP) of the two markets and compare which one is higher after the voting ends. For example, at the end of the voting for a proposal for a new feature, the token price of the "pass market" is higher than that of the "reject market", indicating that the market generally believes that the feature is beneficial to the DAO, and the proposal is adopted. Otherwise, it is rejected.

The key point is that all transactions in the proposal market are conditional:

If you buy DAO tokens in the "Pass Market", the transaction will only be completed if the proposal is finally passed, otherwise your stablecoins will be refunded;

If you sell DAO tokens in the "Reject Market", the transaction will only be completed if the proposal is finally rejected, otherwise the tokens will be refunded.

Because of this, every transaction carries real economic risk exposure. For example, in the case where a proposal is finally passed:

Traders who buy "through the market" will increase their exposure to the token. If the proposal increases the value of the DAO, the buyer will benefit, otherwise they will suffer greater losses;

Traders who sell "through the market" reduce their exposure. If the proposal is not favorable to the DAO, he will be protected from losses.

Therefore, market prices no longer reflect "empty talk" but judgments that are truly supported by money.

Here is a diagram of the life cycle of a Futarchy proposal transaction:

The same situation occurs when the proposal market fails:

More than just deciding the outcome of a proposal, Futarchy governance votes are powerful information markets in their own right.Because it forces participants to “put their money where their mouth is,” Futarchy aggregates scattered knowledge and sentiment into economically backed signals, a mechanism that often leads to more robust decisions than “risk-free voting.” This market-driven feedback provides builders with direct insight into how the collective feels about the value of their proposals.

For investors, Futarchy provides a unique way to directly express their subjective views on DAO decisions, and to increase or decrease their holdings based on the market’s consensus on the DAO’s optimal path. This is especially significant in the context of early-stage DAOs, whose valuations are highly subjective and largely determined by the decisions they make and the direction of the final product.

Futarchy also means that all participants on the equity table can adjust their holdings based on their conviction about specific decisions, enabling continuous alignment of financial interests with strategic direction. This dynamic naturally fosters a “belief-weighted” equity structure: those whose views are consistently aligned with successful decisions will have their holdings naturally strengthened by market forces, while all holders can always maintain their desired, belief-weighted exposure to the strategic direction of the DAO.

Characteristics of Startups and Early-stage Projects

To understand how Futarchy governance benefits builders and investors, we need to first define several key characteristics of early-stage companies:

Subjective valuation: Early-stage startups are generally not generating revenue immediately and are often building entirely new products. Their value depends on the quality of their products and teams, and their ability to stimulate demand in the future through decisions they make today. Unlike mature companies that can use historical performance and comparable companies to anchor their valuations, startups have few such reference points, and pricing is mainly based on interpreting signals and beliefs based on “intangible” factors.

Decisions based on inferences: Information asymmetry forces founders and investors to piece together fragmented information; teams focused on building often ignore signals from the surrounding ecosystem or competitors. Ultimately, many decisions rely more on probabilistic inferences than hard evidence.

Investor faith: Early investors who have deep, long-term faith in the team’s vision can form a patient, goal-aligned group of holders. In times of market volatility, committed holders help maintain stability and give projects time to realize their vision. In contrast, investors who are opportunistic or lack conviction will sell at the first sign of market turmoil, amplifying volatility and forcing teams to distract from responding rather than focusing on building.

Taken together, these characteristics mean that founders and investors are always “guessing (and paying for)” the right narrative and acting accordingly. Futarchy doesn’t eliminate this inherent subjectivity, but rather embraces it: allowing anyone to trade tokens on the outcome of a DAO’s decisions (go/no), leveraging individual beliefs and turning them into aggregated market signals that the DAO can use. This process transforms decentralized intuitions into unified, weighted predictions, essentially shifting ownership to those with the clearest and most persistent beliefs.

By requiring participants to invest real capital in their opinions, Futarchy transforms the most fragile characteristics of early-stage startups (subjectivity and uncertainty) into a governance mechanism that actively strengthens the project, thereby providing a less arbitrary and more rational path for its development.

How Futarchy complements early corporate governance

Futarchy's benefits to the earliest DAOs are mainly reflected in two aspects:

Provide an economically supported information beacon;

Provide a dynamic cap-table mechanism to directly bind the DAO's strategic path to the holder base.

Information Beacon

As an information beacon, Futarchy can provide signals for the feasibility of an idea through market-reinforced feedback and directly reveal the economic attitude of token holders towards a decision.

Economically Backed Decision Making

Futarchic governance draws on the principles of prediction markets. Just as predictions backed by economic bets tend to be more accurate, decisions backed by economic bets should also produce healthier outcomes, because the quality of the outcomes involves real value. This economic exposure sets a cost for participating in decision-making, reduces arbitrary and bad decisions, and incentivizes participants to put forward more high-quality and information-backed opinions through "voting with consequences."

In addition, this mechanism also allows those with the most accurate predictions to increase or decrease their positions at their own discretion and profit from it, further aligning personal incentives with the overall interests of the DAO.

Not only that, Futarchy allows any on-chain user to participate in voting, thereby reducing information asymmetry and absorbing opinions from outside the DAO holders. It turns voting into a market, allowing anyone willing to take capital risks to participate in the evaluation of DAO decisions. This market mechanism also makes manipulation difficult: anyone who wants to push up or down the market price of a proposal's "pass/no" will create an arbitrage incentive for other market participants to trade in the opposite direction. The more manipulation there is, the greater the incentive for reverse arbitrage.

In addition, this mechanism makes manipulation itself costly, because real money must be invested to change the result, which may result in direct financial losses for the manipulator or a single large holder. The entire structure can thus achieve a level of decentralization that is difficult to achieve with token-weighted voting.

The Voting-Holding Gap

In traditional governance systems, there is a potential disconnect between how people "vote" (and what the organization ultimately does) and how they "allocate capital." Someone may vote against a proposal, but still buy more tokens because they are optimistic about the overall project; someone may vote in favor, but quietly sell because they are worried about execution risk.

This creates a gap between “expressed preferences” in governance and “explicit preferences” in the market, making it difficult for builders to truly understand stakeholders’ true attitudes towards specific decisions, rather than just their overall support for the entire project. This blind spot can lead to suboptimal decisions.

In Futarchy, voting behavior is not separated from market activity, but the buying and selling of tokens itself constitutes voting. When a proposal is put forward, the market will immediately express its attitude of approval or disapproval through the direct buying and selling of tokens linked to the outcome of the proposal. A key difference between this and traditional governance is that in traditional governance, market reactions (such as buying and selling behavior) are usually completely independent of the vote itself, and it is difficult to judge the true motivations behind these market behaviors, or their connection with specific governance decisions.

This integrated design of Futarchy reduces the ambiguity of information about holders’ attitudes and the disconnect between this information and optimal decisions. It allows real opinions and beliefs to be captured directly in the voting mechanism, allowing the DAO to move along the path that best fits the economic sentiment of its group of holders.

Unlike the traditional system of "voting one thing on the surface and trading another set privately", Futarchy combines bets and results into one whole. This relationship is also crucial because once the vote is over, tokens will be transferred directly from the party that does not believe in the decision to the party that believes in it. This not only clarifies market sentiment and applies it directly to the decision results, but also redistributes ownership to those participants who are (theoretically) the most informed and the most convinced, allowing the DAO to dynamically balance its equity structure table during the decision-making process

Belief-weighted market value table

Building a "group of holders who truly agree with the project's vision" is one of the most difficult things for early crypto projects. Most teams have a hard time distinguishing between true supporters and opportunistic speculators, resulting in wild swings in token prices and founders being forced to invest a lot of time and energy managing market dynamics instead of focusing on product building.

The most common early user onboarding strategy today is airdrops: using free tokens to incentivize users to use the product. While this approach can bring initial usage activity and improve metrics, it creates some serious problems that undermine the foundation for long-term success:

Opportunistic behavior: Airdrop recipients typically only engage in minimal, inorganic interactions in order to meet the conditions for receiving the airdrop, and then sell immediately after receiving it. This cultivates a group of holders who only want to make a quick arbitrage, with little real belief in the future of the project.

Ambiguous product-market fit signals: When users use the product primarily for financial rewards rather than real needs, the feedback the team receives about the quality of the product and market demand is misleading. Almost any product can be “used” if there’s free money, which makes it hard for teams to tell if the core product actually solves a real problem.

Starting from scratch: After airdrops are over and opportunistic users exit, projects often find themselves back to square one, without a real community left. That brief burst of user activity doesn’t lay much of a foundation for sustainable growth.

This dynamic leaves early-stage projects in a paradox: they need users to prove traction, but the methods used to acquire users often bring in the very people who are least conducive to long-term success.

How Futarchy solves the holder commitment problem

Futarchy uses market-based governance mechanisms to create a “natural selection of holders” to address the problem of insufficient conviction. Over the course of successive governance proposals, token supply will gradually flow to those voters who are “most accurate” (i.e. on the right side of the market) and have the strongest convictions, while holders who are correct but have weaker convictions and those who are wrong (on the wrong side of the market) will slowly lose relative share of the cap table.

This change is gradual (no one is completely wiped out in a single proposal), but will continue to happen over time. When Futarchy is used in conjunction with a more organic token issuance mechanism, the DAO’s holder base becomes more committed and stickier as the project grows.

Futarchy transforms the subjective, hard-to-quantify disagreements around DAO decisions into voluntary, conditional ownership exchanges, with the transaction price being the aggregated perception of the outcome by market participants. Over time, this will increasingly concentrate token ownership in the hands of those who are seen by the market as the “most accurate” and the “most committed” to the future direction of the DAO.

Suppose there is a proposal to add a new feature to the protocol, and three holders have different opinions:

Alice: wants to buy 1 token when the proposal "fails" because she believes this feature is harmful to the DAO. She hopes to have more exposure if the proposal is rejected.

Bob: wants to sell 1 token when the proposal "fails" because he believes this feature is good for the application. If the proposal does not pass, he hopes to reduce his position.

Eve: wants to buy 1 token when the proposal "passes" because she believes this feature will bring value. She hopes to get more exposure if the feature is implemented.

If the market ultimately determines that the proposal should "fail" (i.e., the fail price is higher than the pass price), Alice will effectively "get" 1 token from Bob in this synthetic market. Both of them bet on the outcome of "proposal failure" in the market:

The result is that Alice increases her position and Bob exits this part of the equity structure table. Both of them achieve the results they want. At the same time, Eve's buy order is based on the condition that the proposal "passes", and no actual transfer occurs this time, but her relative influence is diluted by Alice on the equity structure table.

This automatically produces three different outcomes:

Alice (high conviction, traded on the right side of the market): gains more tokens and equity.

Bob (low conviction, traded on the right side of the market): loses tokens and exits the equity.

Eve (did not bet on the right outcome): her absolute position remains unchanged, but her relative equity is diluted by Alice.

This outcome is automatically achieved through conditional markets, an elegant mechanism that allows ownership to flow naturally to those whose judgment is consistent with the collective wisdom of the market. It does not attract short-term arbitrageurs like airdrops, nor does it separate voting from participants' perception of the economic prospects of the decision like traditional governance does. Futarchy ensures that influence is concentrated in the hands of participants who have both conviction in the decision and market recognition.

Ultimately, the equity structure table will become more and more "conviction-weighted" and "accuracy-weighted" over time, composed of holders who repeatedly use capital to support their judgment and prove that they truly believe in the direction of the project.

Limitations of Futarchy

Futarchy is not a guarantee of success. It is just a means to achieve better decisions and a better holder structure, not the ultimate goal. The team still needs to truly execute based on the insights generated in futarchy governance; the idea of the project itself must be reasonable; and there must be a real market demand for the product.

Furthermore, introducing market mechanisms into governance does not guarantee that a DAO will make the best decision every time. The idea of Futarchy is to create an environment where there is an incentive to make the best decisions by giving opinions monetary consequences. But people can still act irrationally, and the market can still misprice decisions.

However, compared to "risk-free" token voting, which gives holders almost no financial cost in guiding the strategic direction of the DAO, Futarchy provides a more incentive-aligned way of making decisions.

The main value of Futarchy is not to guarantee that all decisions will lead to higher token prices or user growth - no governance system can do that. But Futarchy can provide DAOs with a higher probability of success than traditional alternatives.

Conclusion

Futarchy provides a strong governance framework for early-stage startups, giving economic backing to decision-making and enabling investors to align their financial exposure directly with the direction chosen by the DAO.

This mechanism is particularly beneficial for startups, as it provides a more efficient way to cold-start applications and build a strong base of holders than traditional means. While Futarchy can also bring benefits to mature DAOs, it is particularly valuable for early-stage projects with high subjective disagreements and an urgent need to build a high-conviction holder base.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance