The U.S. economy has demonstrated resilience this year amidst a broad shift in economic policy. The labor market remains near full employment, a measure of the Federal Reserve's dual mandate, and inflation, while still somewhat elevated, has retreated significantly from its post-pandemic peak. At the same time, the balance of risks appears to be shifting.

In my remarks today, I will first discuss the current economic situation and the near-term outlook for monetary policy. I will then turn to the findings of our second public review of our monetary policy framework, as reflected in the revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, which we released today.

Current Economic Conditions and Near-Term Outlook

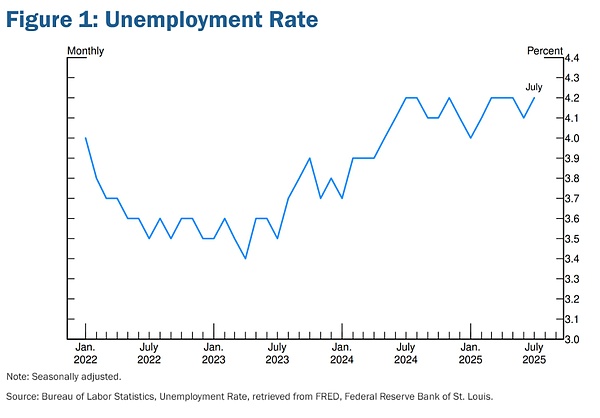

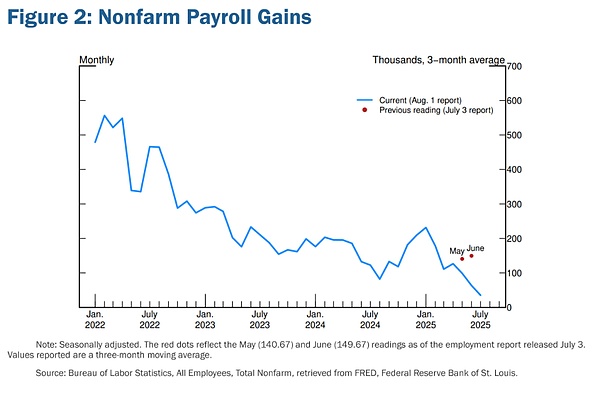

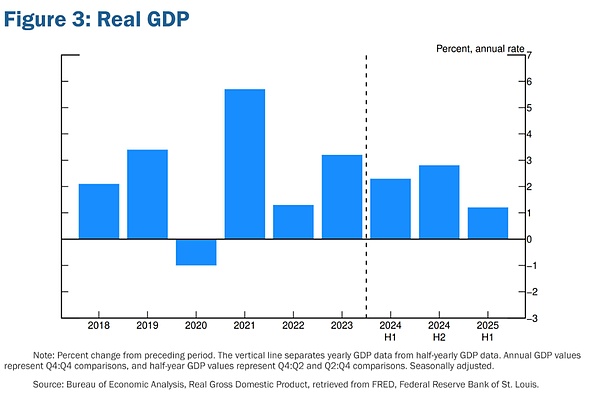

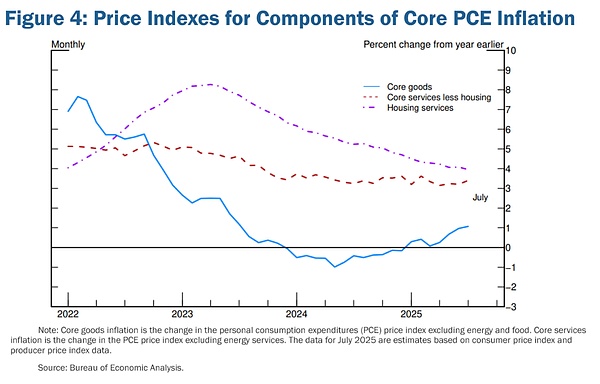

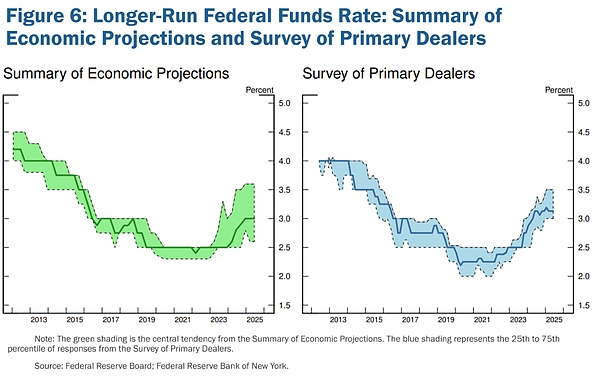

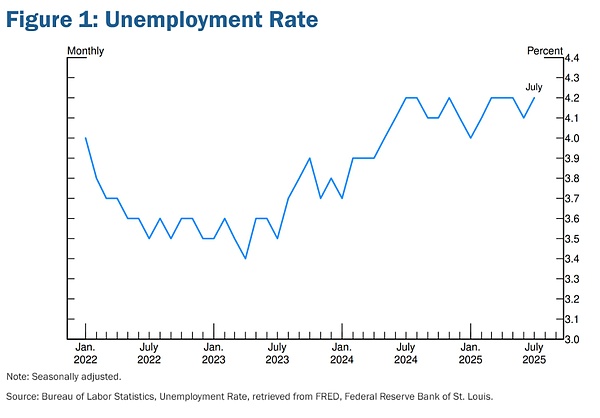

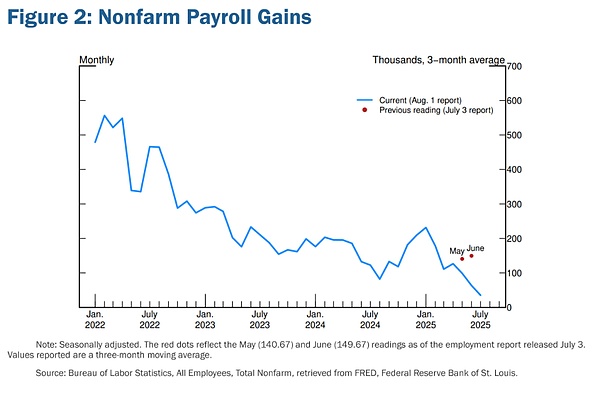

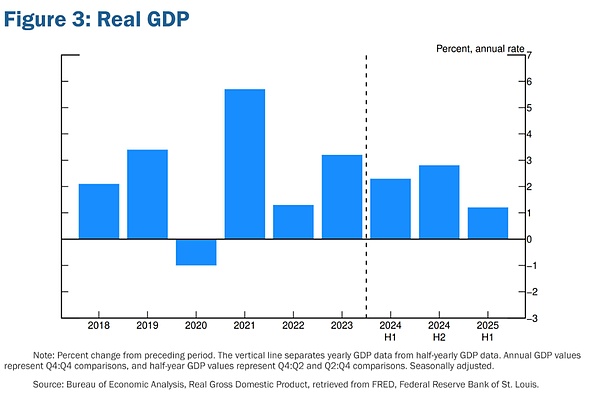

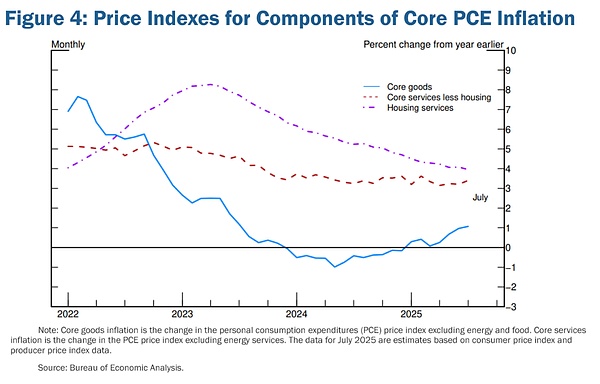

When I took this podium a year ago, the economy was at a turning point. Our policy interest rate had been held between 5.25% and 5.5% for over a year. This restrictive policy stance is appropriate, helping to lower inflation and promote a sustainable balance between aggregate demand and supply. Inflation is already very close to our objective, and the labor market has cooled from its previous overheating. Upward risks to inflation have diminished. However, the unemployment rate has risen by nearly a full percentage point, a rate unprecedented in history except during a recession. Over the next three Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings, we have recalibrated our policy stance, laying the foundation for a labor market balanced near full employment over the past year (Figure 1). This year, the economy has faced new challenges. Significant tariff increases among our trading partners are reshaping the global trading system. Tighter immigration policies have led to an abrupt slowdown in labor force growth. Over the longer term, changes in tax, spending, and regulatory policies are also likely to have important implications for economic growth and productivity. There is significant uncertainty about the ultimate trajectory of all these policies and what their lasting impact on the economy will be. Changes in trade and immigration policies are affecting both demand and supply. In this environment, distinguishing cyclical from trend (or structural) developments is difficult. This distinction is crucial, as monetary policy can seek to stabilize cyclical fluctuations but cannot alter structural changes. The labor market provides a case in point. The July employment report released earlier this month showed that job creation slowed to an average of just 35,000 per month over the past three months, down from 168,000 per month through 2024 (Figure 2). This slowdown was much larger than estimated just a month ago, as early data for May and June were significantly revised downward. However, this does not appear to have led to the significant slack in the labor market that we would have preferred to avoid. The unemployment rate, while rising slightly in July, remains at a historically low 4.2%, having remained largely stable over the past year. Other indicators of labor market conditions have also shown little change or only modest weakness, including quits, layoffs, the ratio of job openings to the unemployed, and nominal wage growth. The simultaneous weakening of labor supply and demand has significantly reduced the "break-even" rate of job creation required to maintain the unemployment rate. Indeed, with a sharp decline in immigration, labor force growth has slowed significantly this year, and the labor force participation rate has declined in recent months. Overall, while the labor market appears balanced, this is an unusual equilibrium caused by a significant slowdown in both labor supply and demand. This unusual situation suggests rising downside risks to employment. If these risks materialize, they could quickly manifest themselves in the form of a sharp increase in layoffs and a rise in the unemployment rate. Meanwhile, GDP growth slowed significantly in the first half of this year, to 1.2%, roughly half the 2.5% growth rate projected for 2024 (Figure 3). This decline in growth primarily reflects a slowdown in consumer spending. As with the labor market, some of the GDP slowdown may reflect a slowdown in supply or potential output growth. Turning to inflation, higher tariffs have begun to push up prices in some categories of goods. Estimates based on the latest available data suggest that overall PCE prices rose by 2.6% in the 12 months ending in July. Excluding the volatile food and energy categories, core PCE prices rose 2.9%, higher than a year ago. Within core inflation, goods prices have risen 1.1% over the past 12 months, a notable shift from the modest decline seen through 2024. By contrast, housing services inflation remains on a downward trend, while non-housing services inflation remains slightly above levels historically consistent with 2% inflation (Figure 4). The impact of tariffs on consumer prices is now clearly visible. We expect these effects to accumulate over the coming months, but their timing and magnitude are highly uncertain. The important question for monetary policy is whether these price increases are likely to materially increase the risk of persistent inflation problems. A reasonable baseline scenario is that the impact will be relatively short-lived—a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, "one-time" does not mean "all at once." Tariff increases take time to be transmitted throughout supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates are still evolving, which could prolong the adjustment process. However, there is also the possibility that upward price pressures from tariffs could trigger more persistent inflationary dynamics, a risk that needs to be assessed and managed. One possibility is that workers, whose real incomes have fallen due to rising prices, could demand and obtain higher wages from their employers, triggering adverse wage-price dynamics. Given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks, this outcome seems unlikely. Another possibility is that inflation expectations could rise, leading to an increase in actual inflation. Inflation has been above our objective for more than four consecutive years and remains a prominent concern for households and businesses. However, judging by market-based and survey-based indicators, longer-term inflation expectations appear well anchored and consistent with our 2% longer-term inflation objective. Of course, we cannot assume that inflation expectations will remain stable. Whatever happens, we will not allow a one-time increase in the price level to become a persistent inflation problem. Taken together, what are the implications for monetary policy? In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, while risks to employment are tilted to the downside—a challenging situation. When our objectives are in tension like this, our framework requires us to balance the two sides of our dual mandate. Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago, and the stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market indicators allows us to proceed cautiously when considering changes to the stance of policy. Nevertheless, with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the evolving balance of risks may require adjustments to the stance of policy. There is no preset path for monetary policy. Members of the Federal Open Market Committee will make these decisions solely based on their assessment of the data and their implications for the economic outlook and the balance of risks. We will never deviate from this approach. Turning to my second topic, our monetary policy framework is based on the unchanging mandate given to us by Congress to promote maximum employment and stable prices for the American people. We remain fully committed to fulfilling our statutory mandate, and the revisions to our framework will support that mandate under a wide range of economic conditions. Our revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, which we call the Consensus Statement, describes how we pursue our dual-mandate objectives. It is intended to provide the public with a clear understanding of how we think about monetary policy, an understanding that is essential for transparency and accountability, and for making monetary policy more effective. The changes we have made in this review are a natural evolution, rooted in our deepening understanding of the economy. We continue to build on the original Consensus Statement adopted in 2012 under the leadership of Chairman Ben Bernanke. Today's revised statement is the result of the second public review of our framework, which we conduct every five years. This year's review includes three elements: Fed Listens events held at Reserve Banks nationwide, a flagship research conference, and discussion and deliberations among policymakers, supported by staff analysis, at a series of FOMC meetings. A key goal in conducting this year's review was to ensure that our framework is appropriate for a wide range of economic conditions. At the same time, the framework needs to evolve with changes in the structure of the economy and our understanding of those changes. The challenges posed by the Great Depression were different from those during the Great Inflation and Great Moderation, which in turn are different from the challenges we face today. At the time of our last assessment, we were living in a new normal characterized by interest rates near the effective lower bound (ELB), accompanied by low growth, low inflation, and a very flat Phillips curve—meaning that inflation was unresponsive to slack in the economy. To me, a statistic that captures that era is that our policy rate remained at the ELB for seven long years, starting in late 2008 after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Many of you will remember the pain of that era, characterized by weak growth and a very slow recovery. It seemed highly likely that even a mild recession would result in our policy rate quickly returning to the ELB and potentially remaining there for an extended period. Inflation and inflation expectations would then likely decline in a weak economy, pushing up real interest rates with nominal interest rates pegged near zero. Higher real interest rates would further drag on employment growth and exacerbate downward pressure on inflation and inflation expectations, creating an unfavorable dynamic.

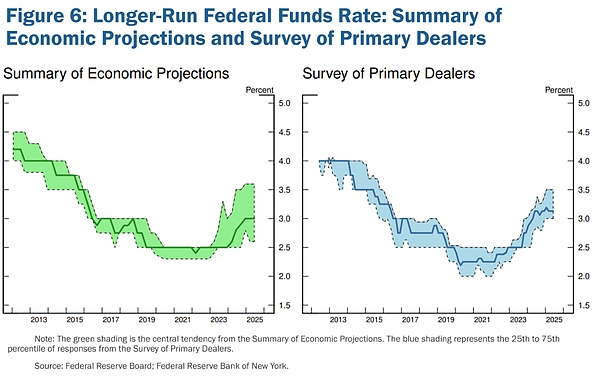

The economic conditions that pushed the policy rate to the effective lower bound and prompted the 2020 framework changes were viewed as rooted in slow-moving global factors that would persist for a long time—and they would likely have if not for the pandemic. The 2020 Consensus Statement included several features that addressed the risks associated with the effective lower bound that have become increasingly prominent over the past two decades. We emphasized the importance of anchoring long-term inflation expectations in supporting our dual objectives of price stability and maximum employment. Drawing on the extensive literature on strategies to mitigate risks associated with the effective lower bound, we adopted a flexible form of average inflation targeting—a "make-up" strategy—to ensure that inflation expectations remain well-anchored even under the constraints of the effective lower bound. Specifically, we stated that after periods of sustained inflation below 2%, appropriate monetary policy may aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2% for some time. As a result, the post-pandemic reopening resulted not in low inflation and an effective lower bound on interest rates, but rather in the highest inflation in global economies in 40 years. Like most other central banks and private sector analysts, until the end of 2021, we assumed that inflation would recede fairly quickly without a significant tightening of our policy stance (Figure 5). When it became clear otherwise, we responded forcefully, raising our policy rate by 5.25 percentage points over 16 months. This action, combined with the easing of supply disruptions during the pandemic, has brought inflation closer to our objective without the painful rise in unemployment that accompanied previous efforts to combat high inflation. This year's assessment takes into account the evolution of economic conditions over the past five years. During this period, we have seen that the inflation landscape can shift rapidly in the face of large shocks. Moreover, interest rates are now well above their levels between the global financial crisis and the pandemic. With inflation above target, our policy rate is restrictive—in my view, mildly restrictive. We cannot be certain where interest rates will stabilize over the long run, but their neutral level is likely higher now than it was in the 2010s, reflecting changes in productivity, demographics, fiscal policy, and other factors affecting the balance between saving and investment (Figure 6). During our review, we discussed how the 2020 statement's focus on the effective lower bound might have complicated the communication of our response to high inflation. We concluded that the emphasis on an overly specific set of economic conditions might have led to some confusion, and we therefore made several important revisions to the consensus statement to reflect this insight. First, we removed the language that indicated the effective lower bound was a defining feature of the economic landscape. Instead, we stated that our "monetary policy strategy is designed to promote maximum employment and stable prices under a wide range of economic conditions." The difficulty of operating near the effective lower bound remains a potential concern, but it is not our primary focus. The revised statement reiterates the Committee's readiness to use its full range of tools to achieve its goals of maximum employment and price stability, particularly if the federal funds rate is constrained by the effective lower bound. Second, we returned to a flexible inflation targeting framework and eliminated the "catch-up" strategy. The idea of intentionally allowing a moderate overshoot in inflation has proven irrelevant. The inflation that arrived in the months following our announcement of the revised 2020 Consensus Statement was neither intended nor moderate, as I publicly acknowledged in 2021. Well-anchored inflation expectations have been critical to our success in reducing inflation without causing a sharp rise in unemployment. Well-anchored expectations facilitate the return of inflation to target when adverse shocks push it higher and limit deflationary risks during periods of economic weakness. Furthermore, they allow monetary policy to support maximum employment in a recession without compromising price stability. Our revised statement emphasized our commitment to taking forceful actions to ensure that longer-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored, serving both sides of our dual mandate. It also stated that "price stability is fundamental to a sound and stable economy and supports the well-being of all Americans." This theme was reflected loud and clear during our "Fed Listens" events. The past five years have been a painful reminder of the hardships that high inflation imposes, especially on those least able to afford the higher costs of essential goods. Third, our 2020 statement stated that we would work to mitigate "shortfalls" from full employment, rather than "deviations." The use of the word "shortfalls" reflected the recognition that our real-time assessment of the natural rate of unemployment—and, by extension, "full employment"—is highly uncertain. In the late stages of the recovery from the global financial crisis, employment remained above mainstream estimates of its sustainable level for an extended period, while inflation ran persistently below our 2% objective. In the absence of inflationary pressures, tightening policy based solely on uncertain real-time estimates of the natural rate of unemployment may not be warranted. We continue to hold this view, but our use of the word "shortfalls" has not always been interpreted as intended, creating communication challenges. In particular, the use of the word "shortfalls" was not intended to be a commitment to permanently abandon preemptive action or to ignore tight labor market conditions. Therefore, we have removed the word "shortfalls" from our statement. Instead, the revised document now more precisely states, "The Committee recognizes that employment may, at times, be above its real-time assessment of full employment without necessarily posing risks to price stability." Of course, if labor market tightness or other factors pose risks to price stability, preemptive action may be necessary. The revised statement also states that full employment is "the highest level of employment that can be sustainably achieved in the context of price stability." This focus on promoting a strong labor market emphasizes the principle that "durable achievement of full employment leads to broad-based economic opportunities and benefits for all Americans." The feedback we received during our "Fed Listens" activities reinforced the value of a strong labor market for American families, employers, and communities. Fourth, consistent with the removal of the word "inadequate," we have made changes to clarify our approach during periods when our employment and inflation objectives are not complementary. In these cases, we will take a balanced approach to promoting both. The revised statement is now more consistent with the original 2012 wording. We consider the extent of deviations from our objectives and the potentially different timeframes over which we project each goal returning to levels consistent with our dual mandate. These principles guide our policy decisions today, just as they did during the 2022-24 period, when deviations from our 2% inflation objective were of overriding concern. Aside from these changes, there is significant continuity with past statements. The document continues to explain how we interpret the mandate given to us by Congress and describes the policy framework we believe will best promote maximum employment and price stability. We continue to believe that monetary policy must be forward-looking and account for the time lags of its effects on the economy. Therefore, our policy actions depend on the economic outlook and the balance of risks to that outlook. We continue to believe that it is unwise to set a numerical target for employment, as the level of full employment cannot be directly measured and varies over time for reasons unrelated to monetary policy. We also continue to believe that a 2% longer-run inflation rate is most consistent with our dual mandate. We believe our commitment to this goal is a key factor in helping to keep longer-term inflation expectations well anchored. Experience has shown that a 2% inflation rate is low enough to ensure that inflation does not become a concern in the decision-making of households and businesses, while also providing some flexibility for the central bank to provide policy accommodation during recessions. Finally, the revised consensus statement retains our commitment to conduct public reviews approximately every five years. There is nothing magical about this five-year cadence. This frequency allows policymakers to reassess the structural characteristics of the economy and engage with the public, practitioners, and academics on the performance of our framework. It is also consistent with the practices of several global peers. Finally, I would like to thank Chairman Schmid and all his staff for their hard work in making this outstanding event possible each year. Including several virtual appearances during the pandemic, this is my eighth time to have had the honor of speaking from this podium. Each year, this symposium provides the leadership of the Federal Reserve with the opportunity to hear from leading economic thinkers and focus on the challenges we face. The Kansas City Fed made a wise move by attracting Chairman Volcker to this national park over forty years ago, and I am proud to be part of that tradition.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance