Article author: Santisa Article compiler:Block unicorn

Foreword

Clear goals can effectively control risks

Big risks can make you soar, and unmanaged risks will make you collapse

As you climb, the upside will shrink. When the risk exceeds the reward, it is necessary to reduce it in time

Cryptocurrency and history are my two major hobbies. I would say that I spend 80% of my waking hours on these two topics. I have noticed that many of the people we remember are not the ones who "made it" through good risk management. Often, they are the ones who kept increasing their bets until they crashed in spectacular fashion. Julius Caesar, Do Kwon, Alexander the Great, and Sam Bankman-Fried all acted in a similar way. An insatiable appetite for risk brought them to the top of their industries, and that same appetite also led to their downfall. The best performers over the long term are the few who are able to switch between risk taking and risk aversion depending on changing circumstances and the achievement of their goals.

This article begins by exploring two important adventurers and managers from ancient history, and their modern counterparts in the cryptocurrency industry. We will discuss some of the gamblers, the megalomaniacs, and the survivors who actually adjusted their bets to their goals and appropriately reduced their risks once they had achieved them.

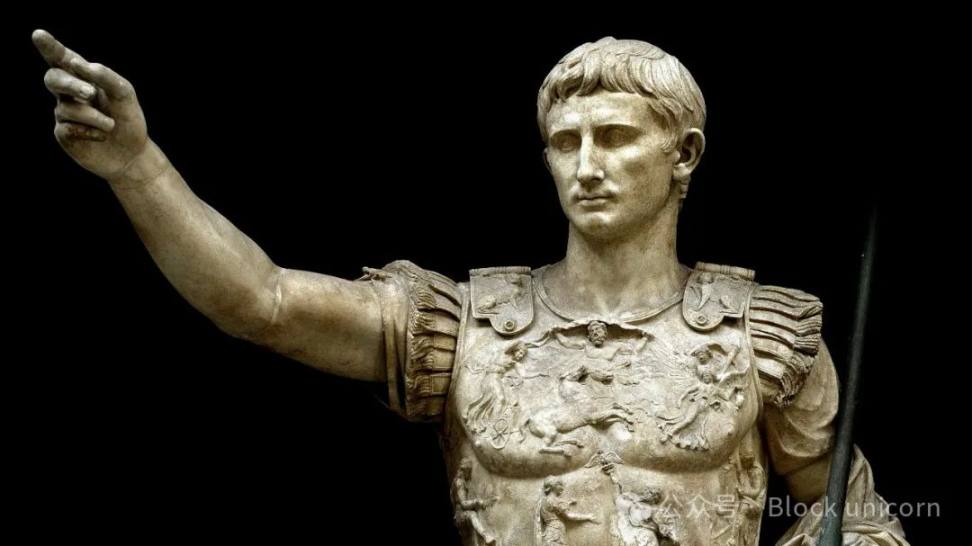

The Original High Roller: Gaius Julius Caesar

Caesar was a mid-level Roman noble who built his career on a combination of charisma, brilliant strategy, and—most importantly—massive debt. He worked his way up the ladder, eventually becoming consul, but rather than wait years in each position, he took on huge risks and debts to speed up his progress. After becoming consul at age 41, he leveraged up and bribed his way to a five-year term as governor of Gaul in 58 B.C. in order to avoid legal and financial reckoning. His debts at the time were equivalent to about 10% of Rome’s annual tax revenue—roughly 133,333 soldier-months’ pay, or about $333 million today*. (* The conversion assumes a Roman legionnaire earned 900 sesterces a year, which, for simple math, equates to $30,000 for the average modern American soldier.)

Maximally leveraged, Caesar invaded Gaul. Failure meant bankruptcy, exile, or execution. While besieging Alesia, a 250,000-man reinforcement army approached from the rear. Any sane general would have called off camp. But Caesar was not only hubristically confident after his meteoric rise, he had no choice: He was deeply in debt, both financially and legally, and his term as governor (which gave him immunity) was about to end. So he doubled down, held his ground, and built an outer wall. Now, some 70,000 Romans faced some 320,000 Gauls**. (** These numbers of soldiers are estimates provided by ancient Caesar and may be exaggerated.)

Alesia was a fortified city in northern Gaul, the last stronghold of the Gauls, led by Vercingetorix, in their fight against Roman rule.

Caesar had won. Gaul was conquered. The victory had brought him great wealth—at least on paper—but much of it was locked up in illiquid assets (mostly slaves). As his term as governor drew to a close, the Senate issued an ultimatum: “Return to Rome to answer for your crimes (and debts).” Caesar always took advantage of opportunities he saw; consequences could be dealt with later. Now that was “later,” and he felt he had no choice. He once again put his life on the line, leading a legion across the Rubicon, declaring “the dice is cast” (alea iacta est).

The Rubicon marked the border of Italy proper, and crossing it meant declaring war on the Senate.

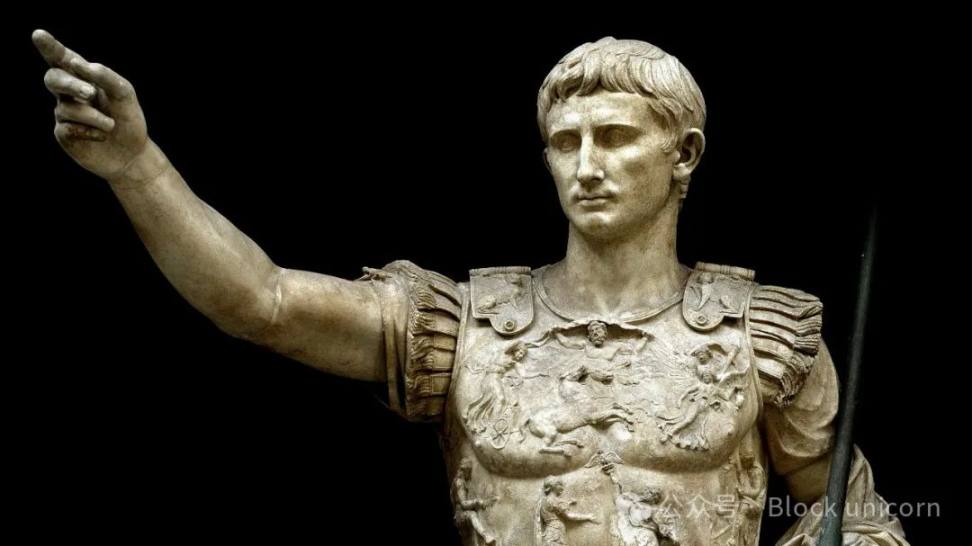

No one expected this bold and unprecedented move. Rome had no garrison; he had captured the city, fought a civil war, and won. He was now the sole ruler of the Roman world. But not content, he aimed for the title “King of Rome.” Ignoring the Kelly Criterion (you should only bet the portion of your capital that is proportional to your edge, beyond which long-term bankruptcy is inevitable), he once again went all in. This final trade blew up his account: instead of an email from Binance, he was stabbed twenty-three times by a group of senators. The risk appetite that propelled him to the pinnacle of power also cost him his life.

The Rise of Octavian

Caesar adopted his 18-year-old nephew Octavian after his death, but Caesar's general Mark Antony blocked the inheritance. Octavian borrowed against his estate to raise about $2.5 billion—about 750% of Caesar's original debt—to boost his popularity and build an army. It looked like Caesar 2.0, but it was a calculated move with a clear goal: Octavian pursued clear goals, not games for the sake of games.

Octavian changed his name to Gaius Julius Caesar, and later Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus. Roman names are complicated, so for this article we’ll just call him “Octavian.”

He knew that standing still could mean death; taking on debt and risk gave him a chance to survive and succeed. He fought and won more civil wars—first against the Senate, then against Antony. After becoming the sole ruler of the known world, he realized the diminishing returns of further risk-taking. He rejected the title of "king" in favor of becoming "princeps," publicly showing respect for the senate while secretly pulling the strings. Once he achieved his goal, he transformed himself from a highly leveraged risk-taker to a conservative administrator, ruling Rome for four decades and establishing a dynasty that lasted nearly a hundred years.

In every journey, a clear goal controls risk. If you don't know what "win" is, how can you win? The goalposts keep moving unless you keep them fixed.

Continuous gambling is addictive; whether out of necessity or sheer pleasure, we keep justifying more risk until we become our own worst enemy.

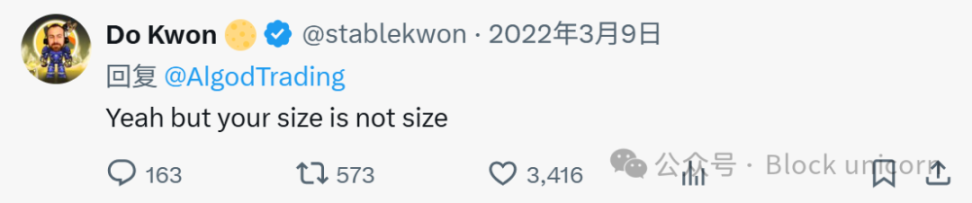

Do Kwon

Similar to Caesar, Do Kwon was born into an elite Korean family. He built his career on charisma, strategy, and—again—massive leverage.

The Terra/Luna reflexive stablecoin system he created relies on perpetual debt. Every dollar the system absorbs creates a greater liability, so there is not enough capital to close out the game. Every UST milestone was achieved with borrowed capital; unlike Caesar, Do Kwon had no "Gallic" to conquer - no calculated bets, just leverage for leverage's sake. He took the risk to the end and ended up in a bleak prison cell in Montenegro. What cost Caesar his life also cost Do Kwon his freedom.

Do Kwon was arrested in Podgorica on March 23, 2023, trying to flee to Dubai using a fake passport.

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF)

SBF, the founder of bankrupt exchange FTX, used customer funds to prop up the platform, buy global influence and finance various risky projects while living a lavish life. He raised $1.8 billion, pushing FTX's valuation to $32 billion, and maintained direct ties with Washington. Like Octavian, he took huge risks with a mindset of world domination. But Octavian learned from Caesar’s fatal overextension, and SBF didn’t: He went all-in, again and again. If he had pulled back, he could have paused his fraud and slowly filled the hole in FTX’s balance sheet; but he doubled down and lost it all. His end didn’t have to be so tragic.

SBF enters court in New York in 2023.

Changpeng Zhao (CZ)

CZ bet everything on speed and regulatory gray areas. He raised money for Binance through an ICO in mainland China. Binance took full advantage of regulatory arbitrage: allowing KYC-free deposits and trading, listing trading pairs arbitrarily, and offering 125x leverage on unpopular trading pairs - running a casino, so to speak.

The future backlash was obvious and inevitable. CZ's bet was that he would grow big enough to make it all worthwhile and have enough capital (both financial and political) to mitigate the consequences. That reckoning came in 2024, when he was sentenced to four months in a minimum-security prison in the United States and Binance was forced to pay a $4.3 billion fine. It can be said that SBF found leverage in customer deposits, while CZ found leverage by exposing himself to enforcement actions. It is safe to say that if Binance had not grown to its current size, the regulatory measures he faced would be more similar to the decades-long prison sentences faced by Tornado Cash developers, and the industry would view the "best ever" CZ very differently.

Conclusion

Caesar’s goal was constantly moving upward as he succeeded, so he needed infinite leverage—statistically, it was only a matter of time before he went bankrupt. Octavian, on the other hand, risked his entire portfolio early on (it was the best time to risk, with minimal risk capital), and abandoned risk as capital grew and returns shrank relative to his goal.

Do Kwon built his entire system on leverage, not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself. Like Caesar, he was eventually “forced liquidated.” SBF’s path didn’t have to be so tragic. He made ethically questionable, highly illegal, and extremely leveraged decisions—although nearly all great historical figures did the same. The key difference is that he failed to reduce risk as returns decayed. CZ, on the other hand, mastered this.

Leverage is an extremely powerful tool. If used properly, it can maximize the opportunity for positive expected value and facilitate life-changing decisions. However, misjudgment or excessive leverage can ruin you. My biggest takeaway is that turning leverage into a habit - becoming numb to unleveraged returns - statistically leads to ruin. Increasing targets will eventually take you far below your initial goals. Clear goals can effectively control risks.

"Every battle has an element of luck; ignore luck, and disaster will follow" - "Rome: Total War" loading screen

Anais

Anais