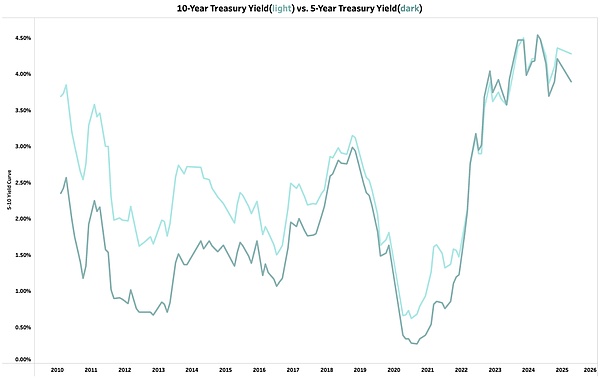

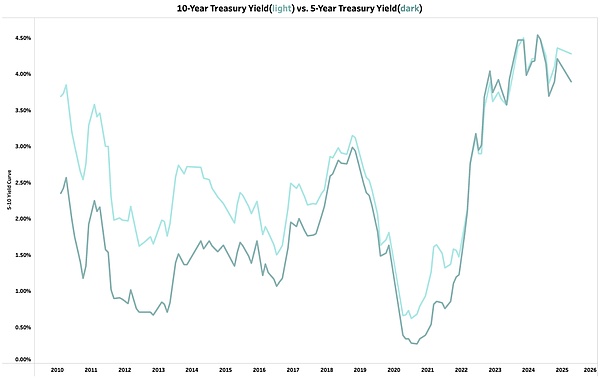

Over the past 12 months, the U.S. Treasury yield curve has steepened, moving out of an inversion (i.e., yields below 0%). An inversion is often viewed as a recession signal, and steepening has preceded recessions many times in history, such as before the global financial crisis in late 2007, before the dot-com bubble burst in early 2001, and before the Great Depression of the 1930s. However, in most cases, a recession occurred within 12 months of the steepening, but as of the steepening that began in mid-2024, a recession has not occurred yet. U.S. real GDP growth remains at 2% per year, and the unemployment rate remains at 4.2%, within the full employment range defined by the Federal Reserve System. The stock market is close to its all-time high, just a few percentage points below, which is not typical of a recession.

One view is that economic data may be about to reverse, GDP growth may decline, unemployment may rise, and the stock market may fall. Another view is that the yield curve may not effectively predict a recession this time. To analyze this, we need to explore why the yield curve is often regarded as a reliable indicator of economic recession.

When the yield curve inverts, short-term interest rates are higher than long-term interest rates, which is mainly affected by the Federal Reserve System's adjustments to the federal funds rate. The inversion leads to tighter credit conditions, banks reduce lending to individuals and businesses, slow economic growth, and may trigger a recession. This process usually takes 12 months. Conversely, when the yield curve is steep (short-term interest rates are much lower than long-term interest rates), credit conditions are easy, banks lend more, and economic growth is boosted.

This is true in theory and verified in practice by the data. A line shows whether the U.S. economy is growing or contracting at any point in time: above zero means growth, below zero means recession. The current economic growth rate is about 2%. If you move the yield curve data forward 12 months and compare it with the economic growth line, the two are almost completely consistent. The rise or fall of the yield curve usually corresponds to an increase or decrease in the economy 12 months later, showing its strong predictive power as a macroeconomic indicator.

However, the indicator is not perfect. Historically, the yield curve inversion has occasionally not led to an economic contraction, but in most cases, a recession occurred within 12 months of the inversion. Since the end of 2022, the yield curve has been inverted continuously, but the economic performance has remained solid. We are still in a "dangerous period" because the yield curve was still inverted a year ago, which means that the economy may slow down in the coming months. Until October 2024, the yield curve will begin to steepen and get rid of the inversion, so the recession signal may still be in effect until October 2025, and the next five months will verify whether the signal is invalid.

To judge whether a recession is likely in the next five months, it is necessary to analyze why the economy has avoided a recession so far. One reason is that when the yield curve inverted at the end of 2022, the US job market was extremely strong, with far more job openings than in the past 20 years and strong hiring activities, unlike the weak job market before the recessions in 2008 and 2001. Since 2022, job openings have fallen by 30%, the job market has weakened, and the economy is more vulnerable to recession than a few years ago, but overall it is still better than before the epidemic.

The second reason is that corporate profit margins are extremely high, reaching historical highs, which is the opposite of the situation before a recession, when profit margins usually fall. Historically, corporate profit margins fell before a recession due to various factors, such as the oil crisis and rising interest rates in the 1970s, the bursting of the technology bubble in 1999, the bursting of the real estate bubble in 2006, and rising oil prices. At present, corporate profit margins have not seen a significant decline, and although they may peak at the end of 2023, they remain high. Certain policies, such as tariffs, may depress profit margins and trigger a recession, but currently high profit margins provide a buffer for the economy, and companies do not need to cut costs drastically in the short term.

Based on current data, the economy may remain stable in the next five months, supporting the continued rise of the stock market. However, if the data changes, the economic outlook needs to be reassessed. Real-time tracking of data and strategy adjustments are crucial to understanding economic trends.

Brian

Brian