Author: Joel John Source: Decentralised.co Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

A friend told me that sometimes the most radical thing isn't to write a manifesto, but to express complex emotions in the most plain language. So today, I'll try to do just that. I'll share my thoughts on how to amplify the crypto industry 100x.

Specifically, I'll explain how industry culture will evolve as crypto moves from niche technology to global financial infrastructure, and what this means for those who first entered the industry. Today's story involves Michelangelo, Hyperliquiquit, and song recommendations from Pakistan.

In short, the risk for crypto is that it could become an overly financialized ecosystem, unable to truly scale beyond its early stages. Trading functionality will be only a small part of the next generation of scalable products. To scale Web3 applications, we must build products that people want to use again and again, for reasons beyond just transactions. Just as only 1% of people on the internet post, it's likely that only 1% of users will transact in native Web3 applications in the future. Crypto is both a culture and a medium of expression. To drive the industry to scale, entrepreneurs must balance both. Here's my argument...

This might be the only place on the internet where Mary Meeker, Jay Z, and Gutenberg are pictured together.

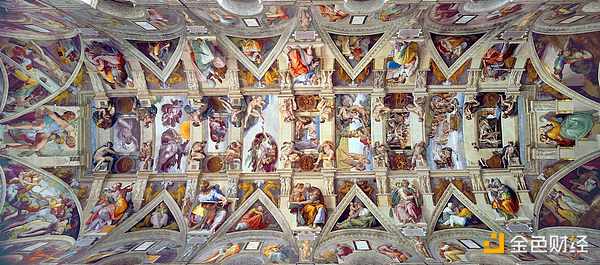

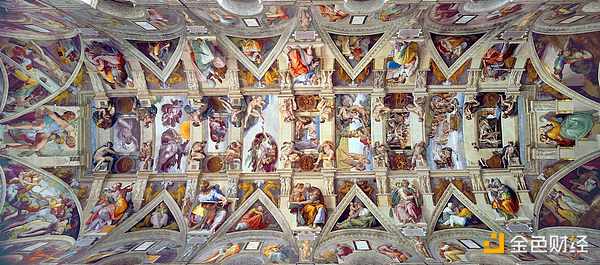

I often wonder what Michelangelo was thinking as he painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling. It's one of the greatest works of art in human history. Initially, he had absolutely no desire to do it. Michelangelo's art was in marble sculpture. Hammer, stone, the human body—that was his playground.

He was in debt after failing to deliver a sculpture for the tomb of a deceased pope when he received a commission from Pope Julius II to paint frescoes for a chapel. Michelangelo felt it was a plot by a rival to embarrass him, as the project was extremely difficult to complete. He was caught in a dilemma: on one side was the commission from the deceased pope, and on the other side was the new request from the living pope.

All of this was created by someone who didn't consider himself a painter. I guess you couldn't just walk up to the head of the Catholic Church and say "no" back then. So he accepted the commission and painstakingly completed the ceiling painting over four years, from 1508 to 1512. He hated the work so much that he composed a poem describing himself as a cat with its back hunched. One line from that poem has always stuck with me: "My painting is dead. Defend me, Giovanni, and protect my honor. I've come to the wrong place—I'm not a painter." It's a familiar experience for anyone who dedicates their life to art: delayed deliveries, working on projects that don't reflect their true desires, and questions about their own worth. But remember, this man who constantly claimed, "I'm not a painter," was creating culture and history. The name Giovanni mentioned in the poem, Giovanni, refers to Giovanni da Pistoia. But there's another Giovanni who's relevant to us—Giovanni de' Medici. He was Michelangelo's childhood friend, and they grew up together. As a teenager, Michelangelo lived in the Medici's Palazzo Riccardi, where he was patronized by Lorenzo de' Medici. The Medici were the most prominent banking family in medieval Europe. Think of them as the JPMorgan Chase or SoftBank of the 15th century, except they were the financial architects of the Renaissance, the "godfathers" of their time. The fact that I can sit here and write about Michelangelo's work, 520 years after his creation, is largely due to the support of the most influential bankers of the time. Throughout history, capital and art have always had an ambiguous embrace, jointly creating what we call culture. Many of the world's most admired works of art are inseparable from the powerful infusion of capital. Michelangelo may not have been the greatest artist of his time. Countless artists throughout history may have been more adept at capturing human emotion, yet we know almost nothing about them. This is partly because they haven't been part of the inner circle of capital; partly because some artists keep their best works locked in sketches. Contemporary media makes this all the more fascinating. The "Sistine Chapel" of our time isn't in Europe, but on the internet. You access them every day: X, Instagram, Substack. Our Michelangelos don't need to wait for the Medicis' approval, but they still hope the algorithms will be on their side. Modern-day Medicis buy churches and plaster their faces on them. For example, Musk boosted the views of his posts after acquiring X. New "gods" are building their churches. Technology can accelerate cultural change. Memes in the age of nine-second videos are the Lego blocks of culture. To scale, culture still requires capital. Without billions of dollars in capital injections, there would be no Facebook, nor would there be the regulatory protections that shield its founders from legal action. Imagine if you could sue Mark Zuckerberg for that racist meme your uncle posted in the middle of the night. Today, technology is a lever for changing culture because it amplifies how humans express themselves. Every technology leaves a cultural imprint because it changes the medium through which people express themselves. I've been thinking about how technology, culture, and capital intersect over time. When a technology achieves scale, it attracts capital. In this process, the way it's expressed becomes less explicit. For example, in the crypto industry, we're no longer chanting "radical decentralization" but more about better unit economics; we're no longer saying "banks are evil" but praising how they distribute digital assets. This shift fascinates me. It impacts everything from how entrepreneurs tell stories to how CMOs shape narratives. But before we delve deeper, let's briefly review the evolution of media itself.

Evolution

Humans are machines of expression. From the moment we first learned to leave traces in caves using leaf sap, we have been constantly carving our messages: about animals, about gods, about lovers, about longing and despair. With the interconnectedness of our media, our expressions have become increasingly vivid.

You may not have noticed, but our logo is a printing press—a manual one. It's a tribute to Gutenberg, yet also carries a satirical twist on the way information is disseminated. When Gutenberg printed the Bible in the late 15th century, he couldn't have anticipated how this invention would boost the distribution of information. For example, by the 17th century, the Annales (or dense scientific works) had become a major literary source in Europe. It was the ability to print and disseminate ideas that fueled the Scientific Revolution. You could discuss the idea that "the Earth is not the center of the universe" without risking your life. As you can see from the word frequency chart above, references to "faith" in literature are declining, and "love" is gradually taking its place. Of course, this isn't to say that all of Europe abandoned religion in search of better partners. Rather, it's the media itself that changed. The very tool that once spread faith—the printing press—may have contributed to its decline. The printing press symbolizes the predictability of how information or technology, once released, can be used and used. The advent of written media transformed reading from a public, social act into a private experience. Around the 18th century, people increasingly preferred reading alone, in silence, rather than aloud. This made sense: before the widespread use of print media, books and literacy were scarce. Back then, reading was often a communal activity: one person would hold a book and read aloud to the group. As books became more affordable and the upper class gained more leisure time, solitary reading became commonplace. This "uncontrolled" spread of ideas sparked moral panics. Families worried that teenagers would spend their free time immersed in romance novels instead of participating in the Industrial Revolution. Media shifted from public affairs to private activities: from temple statues and monastery manuscripts to private handheld pamphlets. The nature of thought also changed: from religion to science, romance, and politics—fields that had little scope for dissemination before the advent of printing. The church, monarchs, and aristocrats had no reason to publish treatises on the workings of power. This may also have contributed to the political revolutions of the late 18th century: both France and the United States decided it was time to change their governance. Without getting bogged down in the details, we still have a whole century of media evolution to trace—radio, television, and the great internet! The commercialization of media also changed with it. Radio and television depended on as many people as possible watching at the same time. This meant they couldn't focus on a very small core audience. Prime-time television was almost always news bulletins, not steamy romances, because that was what families watched together. As a result, the perspectives disseminated often align with the prevailing mainstream acceptance of the time. (There's a scene in The Crown that beautifully illustrates how television was used to bring the Queen closer to the people.) The advent of the internet created limitless reach. Ben Thompson beautifully captured this shift to "endless niches" in an article. In the 1960s, I wouldn't have had the means to write about emerging technologies like debit cards and reach a global audience. As a creator, I was limited to catering to a local audience. But the internet changed all that. I can reach people interested in the digital economy worldwide. Our audience now comes from 162 countries. This is entirely due to the power of the internet. Scale has also changed the way culture is distributed. The Harry Potter series, Jay-Z's "Blueprint" album, Dr. Dre's headphones—they're all exceptional works of art, but it's capital that allows them to compound, becoming centers of culture and capital. In a flywheel effect, capital helps art spread, and art, in turn, helps capital grow. Behind all of this, there's a common factor: technology. Platforms like YouTube, Kindle, and Apple Music help these works reach a global audience. Culture is no longer confined to a single city; it's consumed and recognized by audiences around the world. This significantly expands the audience base and boosts unit economics. The platforms themselves also benefit from attracting users. When it comes to attracting new users, shared culture is the most effective "hook." I've previously written about how SuperGaming leverages well-known brand IP to scale its games. To date, their games have been downloaded over 200 million times. With the advent of AI and algorithmic recommendations, culture has become increasingly centralized. Young people no longer need to actively seek out new media; instead, they risk being drawn into an information vortex, their existing worldviews continuously reinforced by algorithms. This risk is exacerbated by the emergence of large-scale messaging models (LLMs): instead of consuming human-generated content, people engage in direct conversations with chatbots, reinforcing their existing beliefs. This can have serious consequences. Conversely, these tools are also increasingly being used for psychotherapy. This exemplifies the dual nature of the internet. On the one hand, it's the perfect place for a young man from a small town in India to discover a world-class artist and aspire to follow him. On the other, it's also the easiest place to fall prey to bad ideas and be reinforced by harmful content. This explains why society seems increasingly divided. We've lost conversation in favor of algorithmic echo chambers. We've traded "legends" for "content." We've sacrificed depth for niche virality. Who cares about truth if it gets clicks? In an age where everyone has 15 seconds of fame, we've replaced the nuances that make up storytelling with catchy melodies and flashy clips. Stories, emotions, and virtues that once transcended time are now compressed into a dopamine rush between meetings. The human experience has become a series of screen scrolls, like pulling the lever in a modern "content casino." The stories grandmothers once told their grandchildren are gone. Google Gemini has replaced them, because no one has the time or patience anymore. We've replaced handwritten love letters with sarcastic pick-up lines on dating apps—limited, yet heartfelt, physical objects replaced by infinite, yet empty, machine-generated text. So, how does all this translate to the crypto world? To understand this, we must examine the evolution of the industry itself. From Michelangelo to Jay-Z, from the Medici family to SoftBank, one conclusion is almost self-evident: capital drives cultural expansion. When a culture has monetary stability behind it, more people embrace it. Technologies like the printing press, broadcasting, and the internet facilitate its dissemination. Capital is needed both to create art and to build channels for its dissemination. But what if the medium of expression itself is "money"? This is the trillion-dollar question that the crypto world continues to struggle to answer. The original intention of encryption was to replace banks with the values of cypherpunks. This is no accident—many of those who received Satoshi Nakamoto's emails and first read the Bitcoin white paper had run afoul of the government due to their early research on encryption software. In the early 1990s, exporting encryption software was even considered equivalent to exporting nuclear weapons. Therefore, the deep suspicion and hostility toward the government in the early days are completely understandable. Bitcoin's early adopters weren't fintech enthusiasts, but rather drug trading markets like Silk Road and organizations like WikiLeaks that had been expelled from the banking system. In 2011, when WikiLeaks embraced Bitcoin after being blocked by PayPal, Satoshi Nakamoto said they had "stirred up a hornet's nest." Back then, Bitcoin was still a fringe phenomenon. The industry really began to attract widespread attention with Ethereum's ICO in 2014. Cosmos' ICO in March 2017 paved the way for the blockchain craze—everyone wanted to put everything on-chain. Uber? On-chain. Tinder? On-chain. Your local government? Of course, too! We want to put everything on-chain and completely tokenize our lives, because the world needs more decentralization. —Just kidding, but with a hint of sadness. There are two key factors here: Smart contracts on Ethereum make it easy to issue, transfer, and trade assets. On-chain capital formation was a novel concept. Founders could bypass "evil" venture capitalists and raise funds directly from the "community"—of course, the so-called "community" was often just people who wanted to buy tokens and sell them for arbitrage. ICOs gave venture capitalists new exit methods and allowed retail investors to participate. The great promise of the time was that the venture capital business model would be disrupted. The culture at the time revolved around the belief that shared ownership of assets (usually tokens) and distributed governance (usually DAOs) would lead to better outcomes. Like so many chapters in the financial market, those were years of optimism—until asset prices plummeted. As the market evolved, the crypto world gradually split into two user groups: quantitative traders and farmers. Quants are savvy traders who leverage pools of capital, information advantages, and financial knowledge to accumulate wealth. Farmers are the typical user who contributes "labor" to the protocol. I'm a farmer myself; the majority of my crypto assets come from labor provided to the protocol (such as intellectual property). The long tail of farmers are those who go to great lengths for airdrops. You don't even have to actually issue a coin. Just call it "points" and sell a dream. We've gone from initially wanting to overthrow the government to relying on airdrop subsidies in a brutal bear market. Suddenly, the focus wasn't on decentralization anymore, but rather: Which token seemed most valuable? This mirrored the evolution of media: from a medium for private consumption to a symbol of social prestige. The ICO craze faded in 2019, and no one could easily raise funds simply by issuing tokens. However, the market's signaling mechanisms evolved. Token pricing began to depend on: Which VCs invested in it? Which exchanges would it be listed on? Like any emerging industry, we stumbled along the way trying to find our voice. Should I call everyone "ser"? Do I really need to join this DAO call? — It doesn't matter. We saw founders using DAO tokens to buy mansions; Snoop Dogg buying land in the metaverse; maybe I should go to his land and see if Dr. Dre is still Dr. D.R.E. We mistook a crowded Discord chatroom for "community." We debated whether a token was a "product" and used price as proof of product-market fit. We ignored protocols valued at billions of dollars that generated less than $100 in daily revenue. We mistook founders' ability to discuss issues for execution. Worst of all, we mistook technical jargon for a sign of novelty and competence. It wasn't until after the ETF craze, when Bitcoin soared but most altcoins failed to keep pace, that we painfully realized: the emperor has no clothes. The meme coin resurgence of 2024 symbolizes the market's final realization: volatility itself is the product. As long as prices rise, as long as there's a sense of fairness in asset distribution, people will enter the market. Whether it's WIF, Fartcoin, or a bunch of meaningless assets, we're gradually understanding that speculative assets can sometimes be a medium of expression. The common sentiment behind them all is a single desire for profit. Crypto culture has shifted from its initial ideological or technological drivers to the behavioral patterns it unlocks. The focus has shifted to transactions. This makes sense: if the blockchain is the financial rails, then its core purpose should be the efficient and rapid flow of funds. Everything else is a distraction. However, in this process, new alternatives have quietly emerged, revealing the embryonic form of a parallel culture. Most scalable products capitalize on behaviors that seem quirky to outsiders. For example, Layer3 might seem like a playground for airdrop farmers. But if you delve deeper into their business, you'll discover they've built a full-stack Web3 solution serving tens of millions of users: on-chain reputation tools, wallets, exchange functionality, and support for the widest range of blockchains. A platform that seemingly offered "points for completing tasks" has become core infrastructure for early-stage product growth. (I say this because our own portfolio companies frequently use them.) Similarly, NFTs were once considered "outdated technology." But Pudgy Penguins proves otherwise. Its partnership with Walmart has generated over $10 million in revenue. The brand's assets have garnered nearly 120 billion views worldwide, with approximately 300 million of those coming from its IP daily. Pudgy takes a typical crypto-native primitive and transforms it into a completely different approach—building attention through partnerships with retail channels and leveraging Web2 social networks. These products collectively raise the question: What exactly constitutes crypto culture? Is it meaningless meme speculation? Daily forced liquidations in the perpetual swap market? Or—betting everything on a token that just launched last night because, "AI will disrupt jobs, and we must escape the 'permanent middle class' within two years"? The market has already given its answer. Crypto is both a medium of expression and a culture of transaction. Users have embraced it as a stable means of transferring value, which is why stablecoins have become the dominant mechanism for global capital flows. But at the same time, the market has also rejected some concepts. For example, play-to-earn ended disastrously. Or content coins. While I hope they'll become a reality, there's been little progress so far. Every day, I scroll through the content my friends share on Instagram. But I have no idea what my Zora posts are worth. (That's frustrating.) Just as "free speech" can't exist without a few offensive comments, global resource coordination can't be achieved without bad actors exploiting the market. In both cases, actions have consequences. If you do a bad job for a long time, eventually no one will want to listen to you or buy the assets you issue. Ironically, Crypto Twitter may be facing both consequences simultaneously. We have to acknowledge that the evolution of crypto follows a similar trajectory to that of most media. Thousands of books that no one read have long since disappeared. The internet is filled with millions of blogs that no one reads or cares about. Social media works because people post content that often disappears within a day. Cryptocurrencies will be no different. There are over 40 million tokens in existence today, most of which have a reasonable value of zero. One day, content tokens may be missed, just as NFTs are missed today in 2021 or ICO tokens were missed in 2017. For most things, obscurity is the norm. Unless they're tied to culture. Culture is often defined by how we communicate. Language shapes how we perceive and understand the world around us. Until 2021, people communicated using jargon. However, as we strive to reach a wider audience beyond our inner circle, we must use less jargon and more engaging expressions—an art we're constantly honing at Decentralised.co. For example, your dating app can't just emphasize that it's powered by zk-proofs. People just want a "date." The competition between stablecoins isn't about how many chains they support, but rather about users choosing the cheapest and fastest global money transfer mechanism. Consumers care about what they can use today, not what hypothetical layers might exist in the future. As the crypto industry moves closer to consumer products, we must communicate more effectively, using language that ordinary people can understand. Since language is often closely linked to group belonging and frequency of interaction, we must change our approach to user onboarding and retention. The "Medicis" of the new era will be merchants of attention. And the "Michelangelos" of the new era, ironically, will be artists who define the flow of capital. Redemption: One way to understand crypto is to compare it to a casino and a neighborhood café. Casinos are indeed environments where money flows rapidly, where people bet frequently, but ultimately, the house profits most of the time. You rarely see people staying in casinos for long periods of time, at least not most people. In contrast, your local café attracts regular customers day after day. For example, Champaca Café in Bangalore has become a gathering place for people around coffee and books. I wrote many of the first drafts of this article on a chair there, gazing out at the mango trees. Often, the same people return, coffee merely a pretext for gathering. They share stories and troubles, but what truly draws people in is the tranquility and joy of the space. In more religious societies, temples and churches serve a similar function. Coffee, or perhaps faith, is simply a vehicle for bringing people together, but their reasons for staying go far beyond the product itself. Culture is, in essence, the collective stories we share. Today, too many of the stories we share are about price charts. When prices are high, people naturally lack the motivation to return. So, how can we keep people coming back? What levers can we leverage to truly bridge this gap? To understand this, perhaps we need to look back at the internet itself. The internet is being shaped by two forces. One is the content explosion driven by generative AI and large language models. In an era where everyone is a creator, no one is truly a creator anymore. People need new mechanisms to own, monetize, and distribute their content. The other force is verifiability. Endless AI-generated content works in the attention economy (think X or Instagram) because it keeps people engaged longer. More eyeballs, more clicks, more revenue. Ultimately, the value that crypto can bring to the internet can be distilled into two features: verifiability and ownership. This isn't a new idea; we discussed it as early as 2023. But the timing is ripe today because of changes in the regulatory environment and shifting attitudes among capital allocators. The internet has always been a tool for free expression. Crypto empowers people to own their channels of expression and networks, allowing assets to be freely issued, traded, and held. The memecoin craze is essentially what happens when everyone can express themselves in the form of money. When the internet emerged, most people marveled at how it would transform employment. But retail users were truly drawn to the possibilities of entertainment and social interaction, not employment opportunities. Meme assets are like entertainment in the crypto era, but because they suffer from losses, they lack the "Lindy Effect." Perhaps not everything should be monetized. Only about 1% of people on the internet actually publish content. Applying this analogy to crypto, perhaps in some future scenario, users won't actually transact in apps 99% of the time. Bringing users together without transactions as their core value lies the magic of the next generation of consumer apps. I know, it sounds ironic. On the one hand, I emphasize that blockchain is a monetary rail, and everything is a market. On the other hand, I also acknowledge that allowing users to transact frequently will ultimately lead to user churn. Attention, as they say, is perhaps the most scarce resource. What will that look like? Some early observations in the social networking and entertainment sectors: 1. Social networks based on prediction markets. Prediction markets are already experimenting with partnering with major creators, embedding prediction markets within their content and sharing a portion of transaction fees with them. Twitter is even about to integrate Polymarket into its newsfeed. This fusion of attention and transactional economies is driven precisely by the crypto rails. Ultimately, crypto is the only place where you can hedge against the "Will Jesus Return?" question, though it's uncertain whether this can be done on a large scale. 2. Music streaming platforms with better per-play economics. Spotify pays around $0.03 to $0.005 per play, in part because it needs to keep its subscription price low. Allowing creators to issue digital collectibles and collect fees from them could potentially boost revenue. For example, I'd love to own a signed vinyl copy of Fort Minor's "Rising Tied" album. Perhaps in the future, a model could exist where vinyl is issued on-chain but redeemed off-chain. This type of business model already exists in isolated scenarios, like buying game packs on Courtyard, but it hasn't yet been integrated with social or streaming elements. Of course, this doesn't mean that financial primitives aren't important. We discuss revenue-generating applications like Hyperliquid and Jupiter precisely because they serve as modern-day Medici banks. The concentration of capital has given people the tools to experiment with new attention-grabbing tools. But sustaining this requires products that keep people coming back, not just betting. Trading must evolve and go beyond mere speculation. All of this got me thinking—what exactly is culture? Culture is the shared stories we cherish. For example, swapping Pakistani songs with the taxi driver on the way home from work; saving a kheer dessert recipe on Instagram just because my loved one told me her mother always used it to cheer her up when she was sick; when someone asks me for Bollywood movie recommendations, I'll mention "Meet You," "Love Without Borders," or "Lost Ladies" because I think they capture culture so well. Or, when a loved one receives a diagnosis and recovers, I think of visiting the church where three generations of my family have prayed. In these scenes, no money flows. But through shared stories and emotions, a fundamental connection brings us together. It's a sense of belonging that makes everything priceless. These are fleeting expressions, yet they imbue life with meaning. They are the core of my identity, adding, in small ways, to the richness of my life. And this sentiment is reflected in the products.

Look at an Apple product for a long time, and you'll see hints of Steve Jobs's time at Disney. Pick up an iPhone, and you can sense his desire to make something beautiful. It's these details that keep people buying iOS products year after year, even when upgrades are minimal.

Web3 products rarely replicate this underlying culture at scale. In the Web2 era, this was intentional. Facebook, for example, wasn't launched with a points program; instead, it was built around a core of Ivy League graduates, forming its initial cultural foundation. Quora was once the go-to place for developers to gain insights from Silicon Valley. Substack remains the best literary platform on the internet. Web3 products also have their own cultural foundation. Look at what's happening on PumpFun or the discussions on Polymarket, and you'll see a nascent culture taking shape. But like all early-stage fields, it's still hard for it to truly take hold. Remember how I said the internet made love letters the effortless equivalent of text messages? It's also revolutionized how people find love. By 2023, 40% of couples will have met online. Ironically, this demonstrates the nature of technology: on the one hand, it changes the medium through which we express ourselves; on the other, it expands the space for randomness, allowing for more beautiful things to happen. If we cling to the notion that crypto is just speculative applications, we're effectively forgoing the opportunities that randomness can bring. Perhaps it's time to consider crypto as a medium of expression. Perhaps it's time to envision an alternative culture for the industry we've invested so much of our lives in. —— Brewing a Renaissance,

JinseFinance

JinseFinance