Article author: Mario Gabriele Article translation: Block unicorn

The holy war of artificial intelligence

I would rather live my life as if there is a God and wait until I die to find out that God does not exist, than live as if there is no God and wait until I die to find out that God does exist. - Blaise Pascal

Religion is a funny thing. Maybe because it is completely unprovable in any direction, or maybe it's like my favorite saying: "You can't use facts against feelings."

The characteristic of religious beliefs is that in the process of belief, they accelerate at an incredible speed, so that it is almost impossible to doubt the existence of God. How can you doubt a divine existence when those around you believe it more and more? When the world rearranges itself around a doctrine, where is there room for heresy? When temples and cathedrals, laws and norms are arranged to follow a new, unshakable gospel, where is the room for opposition?

When the Abrahamic religions first emerged and spread to every continent, or when Buddhism spread from India across Asia, the tremendous momentum of the beliefs created a self-reinforcing cycle. As more people converted, and as complex theologies and rituals were built around these beliefs, it became increasingly difficult to question these basic premises. It was not easy to be a heretic in a sea of credulity. Grand churches, complex religious texts, and flourishing monasteries all served as physical evidence of the divine presence.

But the history of religion also shows us how easily such structures can collapse. As Christianity spread to Scandinavia, the old Norse faith collapsed in just a few generations. Ancient Egypt’s religious system lasted for thousands of years, eventually disappearing as new, more durable beliefs rose and larger power structures emerged. Even within the same religion, we’ve seen dramatic splits—the Reformation tore apart Western Christianity, and the Great Schism split the Eastern and Western Churches. These splits often begin as seemingly minor doctrinal differences that morph into entirely different belief systems.

Holy Scripture

God is a metaphor for something beyond all levels of intellectual thought. It’s that simple. —Joseph Campbell

Put simply, belief in God is religion. Perhaps creating God isn’t any different.

Since its inception, optimistic AI researchers have imagined their work as creationism—i.e., creation by God. The explosion of large language models (LLMs) over the past few years has further solidified believers’ belief that we’re on a divine path.

It also confirms a blog post written in 2019. Though it was unknown to people outside the AI community until recently, Canadian computer scientist Richard Sutton’s The Bitter Lesson has become an increasingly important text in the community, evolving from esoteric lore to the foundation of a new, all-encompassing religion.

In 1,113 words (every religion needs sacred numbers), Sutton summarizes a technological observation: “The biggest lesson to be learned from 70 years of AI research is that general-purpose approaches to exploiting computation are ultimately the most effective, and by huge margins.” Advances in AI models have benefited from exponential increases in computing resources, riding the giant wave of Moore’s Law. At the same time, Sutton points out, much of the work in AI research has focused on optimizing performance through specialized techniques—adding to human knowledge or narrow tools. While these optimizations may help in the short term, in Sutton’s view, they are ultimately a waste of time and resources, like adjusting the fins on a surfboard or trying a new wax when a huge wave is coming.

This is the basis for what we call the “Bitter Religion.” It has only one commandment, commonly referred to in the community as the "Law of Scaling": exponentially increasing computation drives performance; all the rest is folly.

The religion of Sutton expanded from Large Language Models (LLMs) to World Models, and is now spreading rapidly through the untransformed temples of biology, chemistry, and embodied intelligence (robotics and self-driving vehicles).

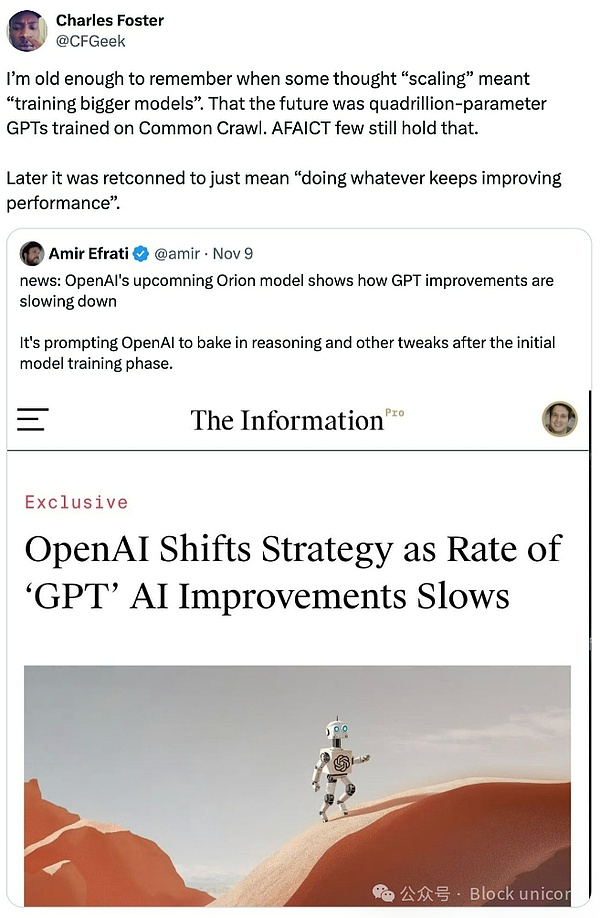

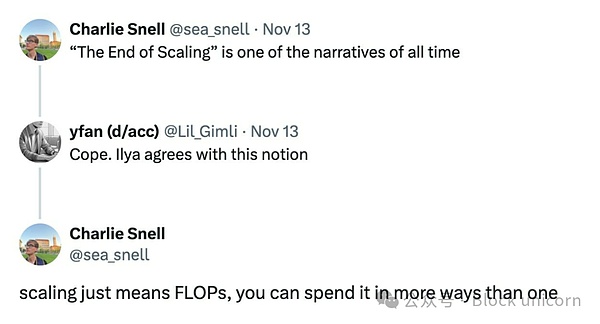

As Sutton's doctrine spread, however, definitions began to change. That's the hallmark of all active, living religions - arguments, extensions, annotations. "The Law of Scaling" no longer just means scaling computation (the Ark is more than just a ship), it now refers to a variety of methods designed to boost transformer and computational performance, with a few tricks thrown in.

The canon now encompasses attempts to optimize every part of the AI stack, from tricks applied to the core models themselves (merging models, mixture of experts (MoE), and knowledge distillation) all the way to generating synthetic data to feed these ever-hungry gods, with plenty of experimentation in between.

Warring Sects

One question that has been raging in the AI community lately, with the air of a holy war, is whether the “bitter religion” is still right.

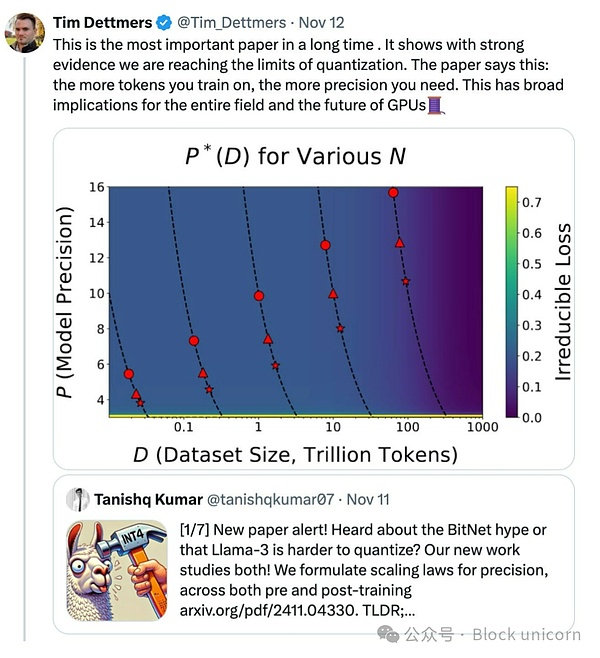

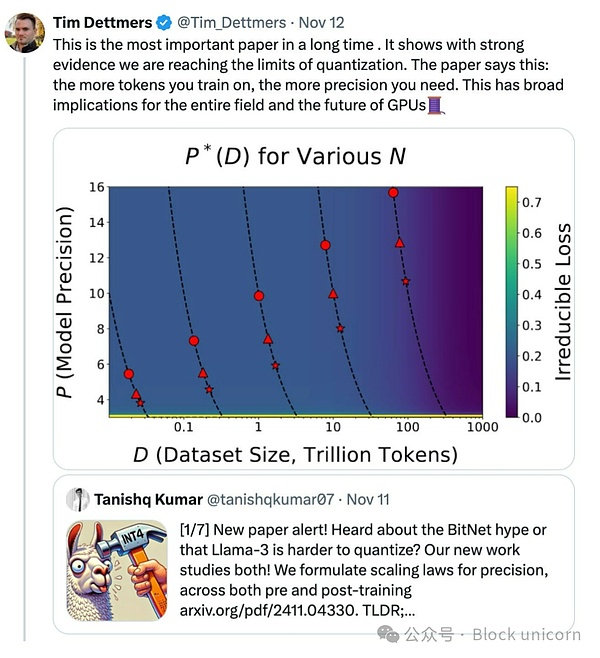

This conflict was ignited this week with the publication of a new paper from Harvard, Stanford, and MIT titled "The Scaling Law of Precision." The paper discusses the end of efficiency gains from quantization, a family of techniques that have improved the performance of AI models and have been a big boon to the open source ecosystem. Tim Dettmers, a research scientist at the Allen Institute for AI, outlined its significance in the post below, calling it "the most important paper in a long time." It represents a continuation of a conversation that has been heating up over the past few weeks, and reveals a noteworthy trend: the growing consolidation of the two religions.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman and Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei belong to the same sect. Both are confident that we will achieve general artificial intelligence (AGI) in the next 2-3 years or so. Altman and Amodei can be said to be the two figures who rely most on the sanctity of the "bitter religion". All their incentives are inclined to over-promise and create the biggest hype to accumulate capital in this game dominated almost entirely by economies of scale. If the law of expansion is not "alpha and omega", the first and the last, the beginning and the end, then what do you need $22 billion for?

Former OpenAI chief scientist Ilya Sutskever adheres to a different set of principles. He, along with other researchers (including many from within OpenAI, according to recent leaks), believes that scaling is approaching a ceiling. This group believes that new science and research will inevitably be needed to maintain progress and bring AGI into the real world.

The Sutskever faction reasonably points out that the Altman faction’s philosophy of continued scaling is not economically viable. As AI researcher Noam Brown asks, “After all, do we really want to train models that cost hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars?” That’s not counting the additional billions of dollars in inference compute expenditures that would be required if we shifted compute scaling from training to inference.

But true believers are well acquainted with their opponents’ arguments. The preacher at your doorstep can easily handle your hedonistic trilemma. For Brown and Sutskever, the Sutskever school points to the possibility of scaling “test-time computation.” Instead of relying on greater compute to improve training, as has been the case to date, “test-time computation” can focus more resources on execution. It can provide more time and compute when an AI model needs to answer your question or generate a piece of code or text. This is the equivalent of shifting your focus from preparing for a math exam to convincing your teacher to give you an extra hour and allow you to bring a calculator. For many in the ecosystem, this is the new frontier of “bitter religion” as teams move from orthodox pre-training to post-training/inference approaches. It’s easy to point out holes in other belief systems and criticize other doctrines without exposing your own position. So what are my own beliefs? First, I believe that the current crop of models will deliver a very high return on investment over time. As people learn how to work around limitations and exploit existing APIs, we will see truly innovative product experiences emerge and succeed. We will move beyond the skeuomorphic and incremental phase of AI products. We should think of it not as “general artificial intelligence” (AGI), which is a poorly framed definition, but as “minimum viable intelligence” that can be customized for different products and use cases.

As for achieving artificial superintelligence (ASI), more structure is needed. Clearer definitions and divisions will help us more effectively discuss the trade-offs between the economic value and economic costs of each. For example, AGI may provide economic value to a subset of users (just a local belief system), while ASI may exhibit unstoppable compounding effects and change the world, our belief systems, and our social structures. I don’t think ASI can be achieved with scaling transformers alone; but unfortunately, as some might say, that’s just my atheism.

Lost Faith

The AI community can’t resolve this holy war anytime soon; there are no facts to bring to bear in this emotional battle. Instead, we should turn our attention to what it means for AI to question its belief in the scaling law. The loss of faith could set off a chain reaction that goes beyond Large Language Models (LLMs) and impacts all industries and markets.

It’s important to note that in most areas of AI/ML, we have yet to fully explore the laws of scaling; there are more wonders to come. However, if doubt does creep in, it will become much harder for investors and builders to maintain the same high level of confidence in the ultimate state of performance in “early in the curve” categories like biotech and robotics. In other words, if we see LLMs start to slow down and deviate from their chosen path, the belief systems of many founders and investors in adjacent fields will crumble.

Whether this is fair is another question.

There is an argument that “general AI” naturally requires larger scale, and therefore the “quality” of specialized models should be demonstrated at smaller scales, making them less likely to hit bottlenecks before they can provide real value. If a domain-specific model only ingests a portion of the data, and therefore requires only a portion of the computing resources to reach feasibility, shouldn’t it have plenty of room for improvement? This makes intuitive sense, but we’ve repeatedly found that the key is often not that: including data, both relevant and seemingly irrelevant, often improves the performance of seemingly unrelated models. For example, including programming data seems to help improve broader reasoning capabilities.

In the long run, the debate over specialized models may be irrelevant. The ultimate goal of anyone building ASI (artificial superintelligence) is likely to be a self-replicating, self-improving entity with unlimited creativity in a variety of fields. Holden Karnofsky, a former OpenAI board member and founder of Open Philanthropy, calls this creation "PASTA" (Process of Automated Advancement of Science and Technology). Sam Altman's original profit plan seemed to rely on a similar principle: "Build AGI, then ask it how to get rewarded." This is eschatological AI, the ultimate destiny.

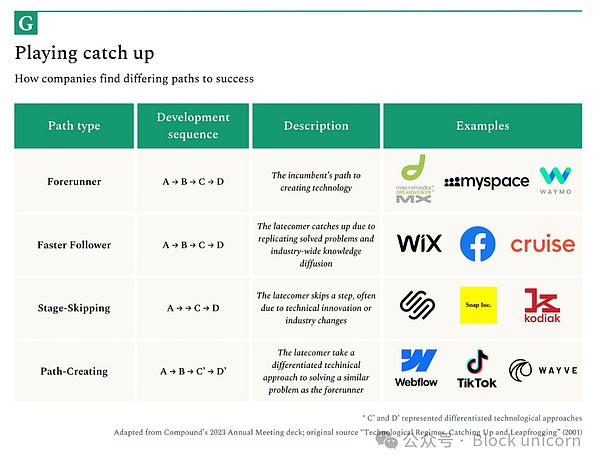

The success of large AI labs like OpenAI and Anthropic has inspired the capital markets to support similar “OpenAI in field X” labs, whose long-term goal is to build “AGI” around their specific vertical industry or field. The extrapolation of this scale decomposition will lead to a paradigm shift away from OpenAI simulations and toward product-centric companies - a possibility I raised at Compound’s 2023 Annual Meeting.

Unlike the eschatological model, these companies must show a series of progress. They will be companies built on scale engineering problems, rather than scientific organizations doing applied research with the ultimate goal of building products.

In science, if you know what you are doing, you shouldn’t be doing it. In engineering, if you don’t know what you are doing, you shouldn’t be doing it. - Richard Hamming

The believers are unlikely to lose their sacred faith anytime soon. As mentioned earlier, as religions proliferated, they codified a script and a set of heuristics for living and worshipping. They built physical monuments and infrastructure that reinforced their power and wisdom and demonstrated that they “knew what they were doing.”

In a recent interview, Sam Altman said this about AGI (emphasis ours):

This is the first time I’ve ever felt like we really know what to do. It’s still going to take a lot of work to get between now and building an AGI. We know there are some known unknowns, but I think we basically know what to do, and it’s going to take a while; it’s going to be hard, but it’s also going to be very exciting.

The Trial

In questioning Bitter Religion, the extension skeptics are reckoning with one of the most profound discussions of the past few years. Each of us has had this thought in some form or another. What would happen if we invented God? How quickly would that God appear? What would happen if AGI (artificial general intelligence) really and irreversibly rose to prominence?

Like all unknown and complex topics, we quickly store in our brains a particular response: some despair at their imminent irrelevance, most anticipate a mix of ruin and prosperity, and a final part anticipates pure abundance as humans do what we do best, continuing to find problems to solve and solving problems of our own creation.

Anyone with a big stake would like to be able to predict what the world would look like for them if the laws of expansion hold and AGI arrives in a few years. How would you serve this new God, and how would this new God serve you?

But what if the gospel of stagnation drives out the optimists? What if we start to think that maybe even God will decline? In a previous post, Robotics FOMO, the Law of Scale, and Tech Predictions, I wrote:

I sometimes wonder what happens if the Law of Scale doesn’t hold, and whether it will be similar to the impact of revenue erosion, slowing growth, and rising interest rates on many areas of technology.

I sometimes wonder if the Law of Scale holds at all, and whether it will be similar to the commoditization curve of first movers and their value capture in many other areas.

“The good thing about capitalism is that we’ll spend a lot of money to find out, no matter what.”

For founders and investors, the question becomes: What happens next?

The candidates who have the potential to be great product builders in each vertical are gradually becoming known. There will be more of them in each industry, but this story has already begun. Where will the new opportunities come from?

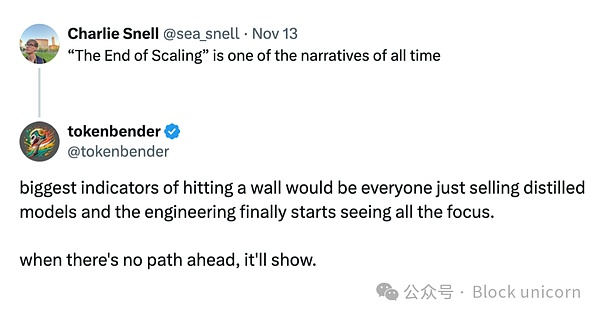

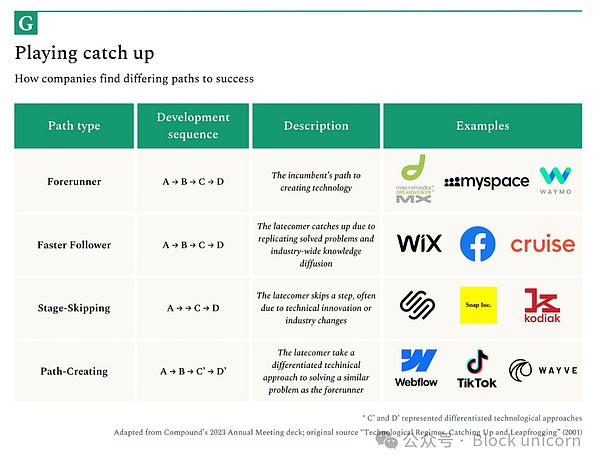

If scaling stalls, I expect to see a wave of closures and mergers. The remaining companies will increasingly shift their focus to engineering, an evolution we should anticipate by tracking the flow of talent. We’re already seeing some signs that OpenAI is moving in this direction as it increasingly productizes itself. This shift will open up space for the next generation of startups to “overtake on the curve” by relying on innovative applied research and science rather than engineering, outperforming incumbents in their attempts to carve out new paths.

Lessons from religion

My view on technology is that anything that looks like it obviously has a compounding effect usually doesn’t last long, and a common view that everyone holds is that any business that looks like it obviously has a compounding effect strangely grows at a much slower pace and scale than expected.

Early signs of religious schisms often follow predictable patterns that can serve as a framework to continue tracking the evolution of Bitter Religion.

It often begins with the emergence of competing interpretations, whether for capitalist or ideological reasons. In early Christianity, different views on the divinity of Christ and the nature of the Trinity led to a schism that produced radically different interpretations of the Bible. In addition to the AI schism we have already mentioned, there are other rifts that are emerging. For example, we see a segment of AI researchers rejecting the core orthodoxy of Transformers and moving toward other architectures such as State Space Models, Mamba, RWKV, Liquid Models, etc. While these are only soft signals now, they show the seeds of heretical thinking and a willingness to rethink the field from fundamental principles.

Impatient rhetoric from prophets can also lead to distrust over time. When a religious leader’s predictions don’t come true, or divine intervention doesn’t arrive as promised, it sows seeds of doubt.

The Millerite movement, which predicted Christ’s return in 1844, collapsed when Jesus didn’t arrive as planned. In the tech world, we often quietly bury failed prophecies and allow our prophets to continue to paint optimistic, long-cycle versions of the future even as scheduled deadlines are repeatedly missed (hi, Elon). However, faith in the law of scaling can face a similar collapse if it is not supported by continued improvement in the performance of the original model.

A corrupt, bloated, or unstable religion is susceptible to apostates. The Protestant Reformation made progress not only because of Luther’s theology, but also because it emerged during a period of decline and turmoil in the Catholic Church. When cracks appear in mainstream institutions, long-standing “heterodox” ideas suddenly find fertile ground.

In AI, we might look to smaller-scale models or alternative approaches that achieve similar results with less compute or data, such as work from various Chinese corporate labs and open-source groups like Nous Research. A new narrative might also be created by those who push the limits of biological intelligence and overcome barriers long thought to be insurmountable.

The most direct and timely way to observe the beginnings of a shift is to track the movements of practitioners. Prior to any formal split, religious scholars and clergy would often maintain heterodox views in private while appearing compliant in public. The contemporary equivalent might be some AI researchers who ostensibly follow the laws of extension but secretly pursue radically different approaches, waiting for the right moment to challenge the consensus or leave their labs in search of theoretically broader horizons.

The tricky thing about religious and technological orthodoxy is that they are often partially right, just not as universally true as their most devoted believers think. Just as religions incorporate fundamental human truths into their metaphysical frameworks, the laws of extension clearly describe what is really going on with neural network learning. The question is whether that reality is as complete and immutable as the current enthusiasm suggests, and whether these religious institutions (AI labs) are flexible and strategic enough to bring the zealots along for the ride. In the meantime, build the printing presses (chat interfaces and APIs) that allow knowledge to spread so that their knowledge can spread.

Endgame

“Religion is true in the eyes of the common people, false in the eyes of the wise, and useful in the eyes of the rulers.” - Lucius Annaeus Seneca

A possibly outdated view of religious institutions is that once they reach a certain size, they, like many human-run organizations, are prone to succumbing to the motive of survival, trying to survive the competition. In the process, they lose sight of the motives of truth and greatness (which are not mutually exclusive).

I have written before about how capital markets have become narrative-driven information cocoons, and incentives tend to perpetuate those narratives. The consensus of the law of expansion feels ominously similar—a deeply held belief system that is mathematically elegant and extremely useful in coordinating large-scale capital deployments. Like many religious frameworks, it may be more valuable as a coordination mechanism than as a fundamental truth.

Miyuki

Miyuki