In February this year, Anthropic, the company that developed the Claude model, completed a unique "field survey of the workplace". They analyzed more than 4 million user conversations and matched them with the U.S. Department of Labor's O*NET occupational database, which records thousands of occupations and 19,530 types of job responsibilities in detail. This data-based matching clearly reveals for the first time how AI is being integrated into various jobs and which positions are affected.

(To protect privacy, the research team used a "privacy protection" system called Clio, which can only analyze aggregated data and cannot access specific personal chat records.)

1. AI's iron fans: not bosses, but "coders" and "writers"

After the research results came out, the first discovery was that the use of AI is extremely "biased". Nearly half of its uses are concentrated in two fields.

Champion: Computer and Mathematics (37.2%)

Yes, AI's number one "iron fan" is code farmers.

Imagine this scene: Programmer Xiao Zhang is developing an e-commerce app, and suddenly the program crashes, and the error message is like a heavenly book that is incomprehensible. In the past, he might have to spend half a day scratching his already limited hair, struggling to find the problem in the ocean of code. Now, he throws the code and the error message to Claude: "Brother, what's the problem?" AI takes one look and replies: "The problem is in line XX, the parameter format is incorrect."

From "developing and maintaining software" to "programming debugging" to "designing databases", these are the things that programmers most often ask AI to help them do. For them, AI is not here to steal their jobs, but more like a 24-hour standby, tireless programming partner.

Runner-up: Arts and Media (10.3%)

Ranked second are those who make a living by writing. This field, which sounds very "liberal arts", actually works very well with AI.

For example, Xiao Li from the marketing department wants to write a product promotion copy. She can let AI "brainstorm" several titles first, and then pick the best one to continue writing. After writing the first draft, she showed the article to AI again: "Please check it for me. Is the language attractive enough? Can it be more lively?" And when she needs to publish an article in a specific format, AI can also quickly complete the typesetting.

This type of users includes technical document writers, advertising copywriters, editors, and even archivists. For them, AI is the perfect combination of inspiration library, proofreader and typesetting tool.

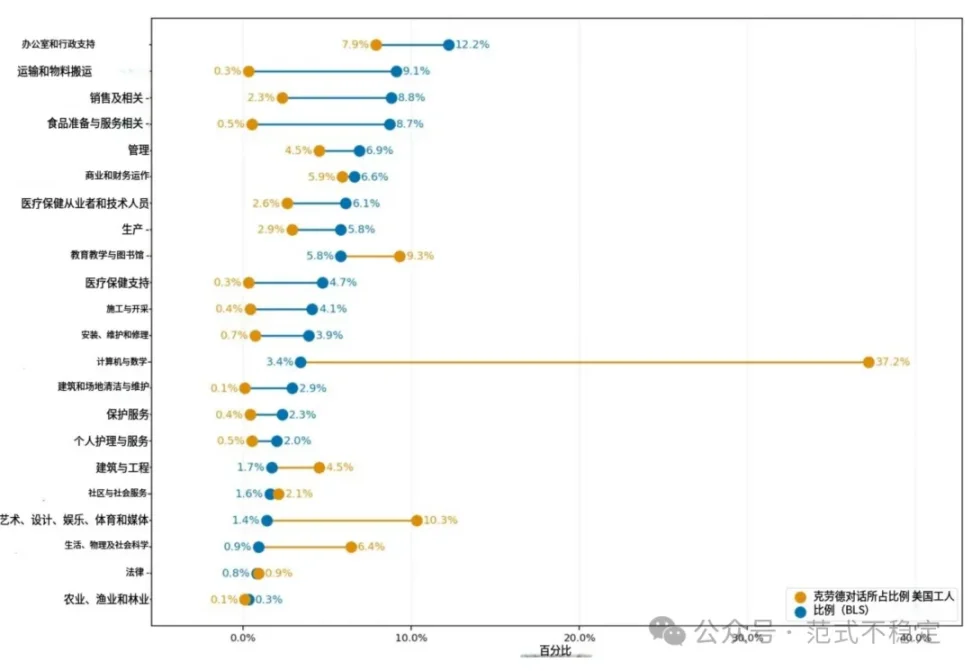

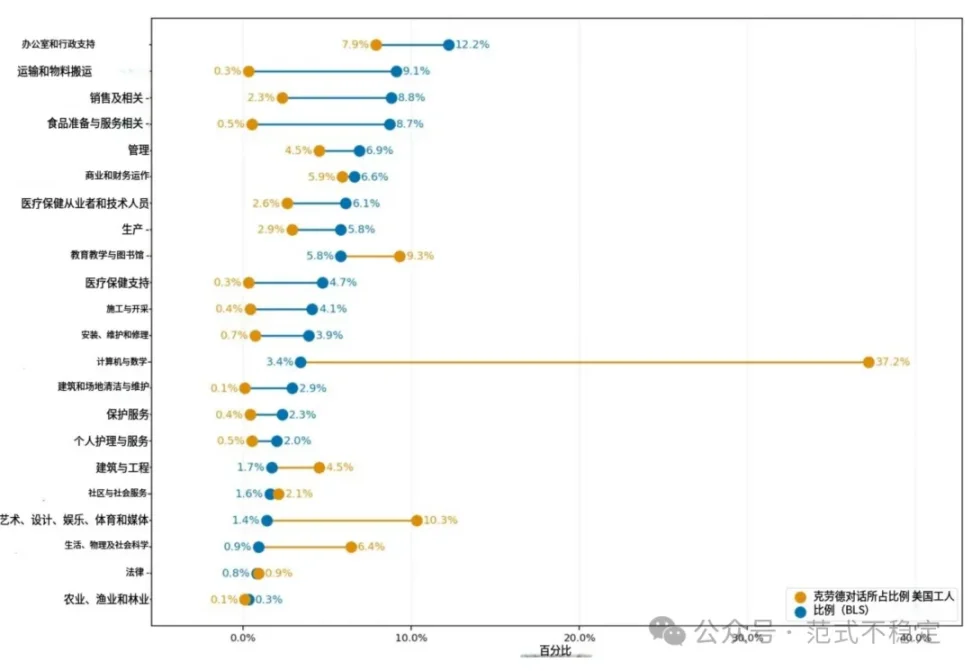

However, the occupational distribution of AI is seriously unbalanced. Refer to the picture below. Computer and mathematics occupations, which only account for 3.4% of all jobs in the United States, account for 37.2% of AI conversations. In contrast, food, sales, and transportation jobs, which together account for nearly 30% of all jobs in the United States, only account for 3% of the total conversations.

The original image is from the Anthropic research dataset. This image is generated using the AI translation tool

Second, is AI a "replacer" or an "enhancer"? Currently more like a "super assistant"

After figuring out "who is using it", the next key question is "how to use it". The report gives an important data: 57% of the usage belongs to "enhancement" and 43% belongs to "automation".

This shows that AI is currently more of an "enhancer". Researchers divide human-machine collaboration into five modes:

Automated behavior (43%)

Command-based: The simplest "automation", just like using a tool. "Translate this paragraph into English", AI directly gives the result, with almost no interaction.

Feedback loop: Commonly used by programmers. The user gives the code to AI, and after running the code and reporting an error, the user feeds back the new situation to AI, and the cycle continues until the problem is solved. People are mainly "messages".

Enhanced behavior (57%)

Task iteration: Deep collaboration. You ask AI to design a webpage. After AI gives the first version, you say: "The layout is good, but the color is too dark. Can it be brighter? The button should also be larger." It's like two colleagues constantly iterating and completing the task together.

Learning: It's not to complete the task, but to acquire knowledge. "Can you explain what a 'neural network' is with a simple metaphor?" AI is an all-round teacher here.

Verification: You have completed the work, but you want AI to help you check it. For example, after writing the SQL code, let AI see if there are any problems with the logic and whether there is a better way to write it.

This ratio of 57% to 43% shows that most of the time we are not passively "served by AI", but actively "controlling" AI. It is more like a powerful external brain, which we use to learn, iterate and verify work, and ultimately make ourselves stronger.

Third, the higher the income, the more AI is used? The answer is "inverted U-shaped"

This may be a counterintuitive discovery. The relationship between the use rate of AI and wages is not a straight rise, but an "inverted U-shaped" curve.

The bottom and top of the pyramid are less used

Low-income occupations: restaurant waiters, construction workers, truck drivers. Their work requires a lot of physical strength and interaction with the real world. AI has not yet grown hands and feet, so it is naturally difficult to participate.

Extremely high-income occupations: surgeons, judges, senior management. These jobs require not only top-level expertise, but also huge responsibilities and risks, and the decision-making process is complex and full of uncertainty. AI is far from reaching this level at present, and there are many regulatory and ethical restrictions.

"Technical white-collar workers" with middle and high incomes are the absolute main force. The peak of AI use appears in those occupations that require "a lot of preparation" but are not at the level of "top experts", such as software developers, data analysts, financial analysts, marketing managers, etc.

This "inverted U-shaped" distribution clearly shows the boundaries of current AI capabilities. It is best at dealing with knowledge-based jobs that have fixed rules, are centered on information and data, but require considerable intellectual investment.

Fourth, AI is blurring professional boundaries and causing "skill inflation"

An interesting finding in the study is that many AI conversations classified as specific professional tasks actually come from professionals who are not in the field. For example, queries classified as "nutritionist work" may come from ordinary people seeking dietary advice, rather than professional nutritionists.

This represents a new trend: AI is blurring professional boundaries, enabling ordinary people to enter fields that previously required professional training. This "professional knowledge equality" may lead to a wider range of knowledge acquisition and application, but it also raises questions about professional value and quality control. When AI allows everyone to be a "half expert", how will the boundaries and value of professional services be redefined?

This also reveals another important trend: AI is creating a new "skill inflation". When AI can easily complete basic programming, "knowing how to program" is no longer an advantage. This will have a profound impact on the job market and even the definition of work in this society. The definition of work itself has been changing. Decades ago, if you said "typing", people knew you were doing a very professional job. But now if you say "typing", people will think you are talking nonsense, because typing itself is no longer considered a professional skill, so the meaning of "working" that was once implied by the three words "typing" has disappeared.

With the development of AI, many skills that we consider valuable today may also undergo similar changes.

Conclusion: Don't be afraid of AI coming to steal your job, but learn how to get along with it

This "war report" from 4 million real conversations paints a more complex and interesting picture than the "unemployment theory".

In general, the AI revolution is not to eliminate a certain profession at once, but a "penetration war". It is quietly changing all aspects of our work with "tasks" as units. Research shows that about 36% of occupations have at least a quarter of their tasks affected by AI. For 4% of occupations, the AI penetration rate of work tasks has exceeded 75%. Although the overall proportion is not high enough, considering that it is only the beginning of the AI era, this penetration speed is already amazing.

This penetration is silent and is happening even in areas that seem to have nothing to do with technology. For example, lawyers may not be completely replaced by AI, but those who do not use AI for case research and document preparation may be surpassed by their peers who make good use of AI.

For each of us ordinary people, the biggest revelation of this report is: at least in the short term, instead of worrying about being robbed of our jobs by AI itself, we might as well worry about being robbed of our jobs by our peers who are better at using AI.

The way forward has thus become clear:

In the short term, we must learn to cooperate with AI, treat it as a highly capable co-pilot and a tireless intern, and let it help us automate repetitive tasks, iterate creative work, verify ideas, and learn new knowledge.

In the medium term, we must learn to be the "boss" of AI. This requires technology: understanding the capabilities of AI, accurately defining problems, breaking down tasks, issuing instructions, evaluating and integrating results, and leading workflows. This is not easy and requires skills and a lot of practice.

In history, each wave of technology has followed the law of "eliminating old jobs and giving birth to new industries." The steam engine eliminated coachmen, but created a huge industry and logistics; electricity made lamplighters unemployed, but opened up a new era of electrical appliances and entertainment.

In the long run, AI will replace repetitive mental work, but this will not devalue human value, but make us more precious. We are no longer just executing, but asking questions; not just processing existing data, but bravely exploring the unknown; not satisfied with imitation, but pursuing original ideas; not relying on cold interactions, but using warm empathy to establish real connections; in the end, what we pursue is not efficiency, but meaning. These are the heights of humanity that algorithms cannot climb.

You don’t have to worry about AI, but you should worry about yourself who can’t use AI.

Kikyo

Kikyo